Background

As the re-sharing and uploading of links of the BBC documentary titled “India: The Modi Question” got banned by the Ministry of External Affairs and the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting (MIB), the guarantee of free speech as envisioned in the Constitution wavered. Their actions are based on allegations of a lack of objectivity, the prevalence of bias, continued colonial mindsets, as well as selective and prejudicial representation of events. Dismissing it as propaganda, the MIB banned re-sharing and uploading of links of the the documentary, by invoking its emergency powers, as defined in Rule 16 under Part III of the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021 (IT Rules, 2021). This was revealed in multiple news reports on January 21, 2023.

The object of contention, a two-part BBC documentary, claims to investigate certain aspects relating to the 2002 Gujarat riots when Prime Minister (PM) Modi served as the Chief Minister (CM) of the state.

With the use of emergency powers, Twitter and Youtube were directed to block access to the first episode of the documentary. Reportedly, Youtube and Twitter, in the face of the threat of sanctions, gave in and complied with the ban. They were also called upon to take down or block subsequent attempts to upload or reshare a link to the video.

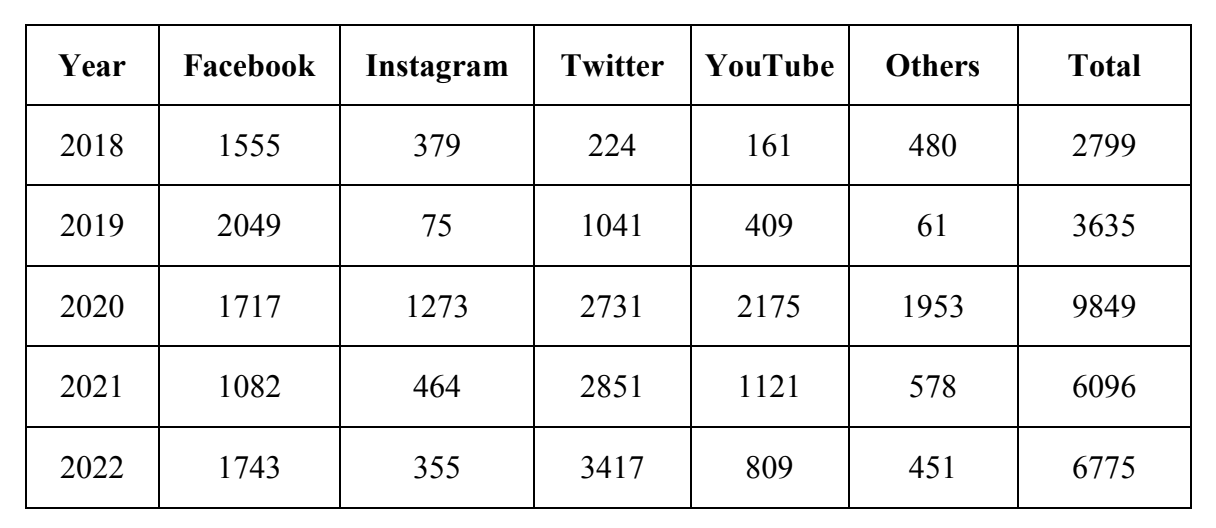

In a written reply dated February 10, 2023, to the Rajya Sabha in the ongoing Budget Session, the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) stated that, in total, internet intermediaries and government agencies blocked a total of 29,154 uniform resource locators (URLs) over the past five years (2018-2022). The data shared in the reply speaks volumes of the ever-so-often usage of the Government's power to censor content.

Source: Response by MeitY in Rajya Sabha dated February 10, 2023

Blocking of the BBC documentary

It is worth noting that these blocking attempts using the emergency provision date back to before the notification of the IT Rules 2021 which empowered the Secretary of MIB with issuing interim blocking directions.Prior to 2021, MeitY exercised its emergency blocking power under the Information Technology (Procedure and Safeguards for Blocking for Access of Information by Public) Rules, 2009. Transparency, in this case, the issuance of press releases, is guided by the convenience of the authorities. In total, roughly seven press releases under emergency powers under Rule 16 have been put up since December 2021. Some of these government-issued takedown orders get to see the light of the day only when some platforms report it voluntarily using mechanisms like the Lumen Database, thereby rendering the process of blocking content via takedown orders opaque. In its 20th Transparency report released in 2022, Twitter revealed that the Union Government made a total of 3,992 legal requests to remove content from its platform.

The following table compiles the press releases put out by the MIB since December 2021, about their use of 'emergency powers' under Rule 16. Inconsistencies among these 8 press releases point to the possibility of there being more instances of blocking, which have not been accompanied with a press release.

Source: Data compiled by Prateek Waghre, Policy Director at IFF

Additionally, the selective issuance of press releases and providing unattributed statements when citizens’ right to access information is curtailed clouds the entire process of blocking content. In the relatively rare instances when disclosures have been made, they have been in relation to controversial topics like Jammu and Kashmir or the censorship of Pakistani content pertaining to the military forces. Not surprisingly, the BBC documentary has been blocked online without the publication of any formal press release. Since the Rules allow for non-publication of legal blocking orders under the confidentiality clause, such orders (including those under Rule 16) rarely get published. In the event of non-publication of official blocking orders, citizens are denied the opportunity to challenge such orders. The need for disclosure also emerges from a joint reading of the Shreya Singhal & Anuradha Bhasin judgments.

Rule 16 confers significant power on the Government to muzzle free expression. An Authorised Officer can examine the content & submit a written recommendation to the Secretary of the MIB, who may then issue directions without hearing the intermediary. The content creator/intermediary is not provided an opportunity to be heard in situations "for which no delay is acceptable".

In the absence of a legislative definition for an ‘emergency’, the increased use of such powers hints at the misuse of censorship powers. Such blocking impinges on our freedom of speech, freedom to practise any profession, and fundamental right to privacy and is manifestly arbitrary and suffers from excessive delegation.

As submitted in T.M Krishna’s case, IT Rules are particularly harmful to artists since the chilling effect the rules create “tend to altogether quell the creative process and makes it impossible for a person to think imaginatively, beyond conventional boundaries, and create art that is politically and socially salient.” The Madras High Court gave credence to the artist’s grievance surrounding the oversight mechanism of the Union Government as the final tier of the process of regulation and laid down in its order that an oversight mechanism to control the media by the Government may rob the media of its independence and the fourth pillar, so to say, of democracy may not at all be there.

IT SURVEY ON BBC OFFICE

The Income Tax Department carried out survey operations at the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) India offices in Delhi and Mumbai for three days starting February 14, 2023, clocking nearly 60 hours. International news organisations like the New York Times have labelled these surveys as a retaliatory move. This branding stems from the usage of government agencies to intimidate and harass press organisations that are critical of government policies or the ruling establishment, the Indian tax authorities' surveys at the BBC’s offices and the seizure of its journalists’ phones weeks after it aired a divisive documentary scrutinising the PM’s role in the 2002 Gujarat riots. These surveys at the BBC were reportedly conducted under Section 133A of the IT Act, 1961, which gives the IT Department the power to carry out “surveys” to collect concealed information.

The powers to conduct search and seizure, and surveys have their origins in Sections 132 and 133A under the Income Tax Act of 1961 respectively. These powers are couched in broad terms, and their exercise without procedural safeguards is contrary to the fundamental right to privacy as enshrined in Article 21 of the Constitution and as recognised by the Supreme Court in the Puttaswamy judgement.

A survey is less invasive as compared to search and seizure and gives the officers limited powers and jurisdiction. Section 133A provides a list of acceptable and prohibited actions that the income tax department can perform. In addition, Section 133A(4) provides that tax officials are not allowed to remove articles, stocks, cash, or other valuables from the premises without prior approval. Even the time-bound (15 days) impounding of property is subject to approval by higher authorities.

The Act limits the scope of the survey to the inspection of books and verification of cash and inventory. It doesn't provide for an indiscriminate seizure of mobiles, laptops and digital gadgets by tax officials during a survey. Only books of accounts and documents can be impounded subject to a reasoned order, though the documents may be in an electronic format. An indiscriminate seizure of mobile/digital gadgets without a reasoned order during a survey goes against the powers conferred under 133A(3) and Section 133A(4). Such impoundment reflects its arbitrariness and encroaches upon the privacy of the taxpayer and its employees. It would've been lawful if, by reason of a speaking order, necessary approvals and safeguards, the survey would have been given the colour of a seizure.

Further, these powers were provided with a view to searches and seizures of objects in the physical world. However, personal digital devices, which contain more sensitive personal data about individuals than any physical space, effectively act as an extension of ourselves. The rationale behind such survey/search and seizure is to be tied to the purpose of the investigation, thereby rendering the reported seizure of a complete device of reporters and journalists of BBC completely disproportionate. Section 133A also does not allow for the sealing of the business premises.

The question is whether surveys are an appropriate method to investigate an alleged violation of transfer pricing rules and diversion of profit. Out of the lesser of the two evils, the most appropriate step to tackle such an allegation would have been to launch a fresh assessment of income or the completion of pending assessments.

Necessity and proportionality are supposed to weigh in when such survey actions are to be used. The adoption of such a measure in the presence of other courses casts a looming shadow over our democratic principles as enshrined in the Constitution. All in all, this seems to be a case of malafide implementation of the tax laws.

The amendments as per the Finance Bill, 2023 in this year’s union budget make matters worse by introducing amendments that will allow the authorised officer to requisition the services of ‘any approved person or entity’ which may include experts in the field of data forensics. Thus, it ends up expanding surveillance powers. Without effective legislative limitations and safeguards to prevent access to certain types of personal information IT officials have been empowered to seek the assistance of experts to access digital devices and encrypted data. The invocation of these powers by the executive requires oversight and in its absence, such broad authorisations increase the scope for arbitrariness and misuse. The lack of regulation over the broad and unchecked powers of the State authorities to seize and examine personal digital devices violate the right to privacy and the constitutional guarantee against self-incrimination.