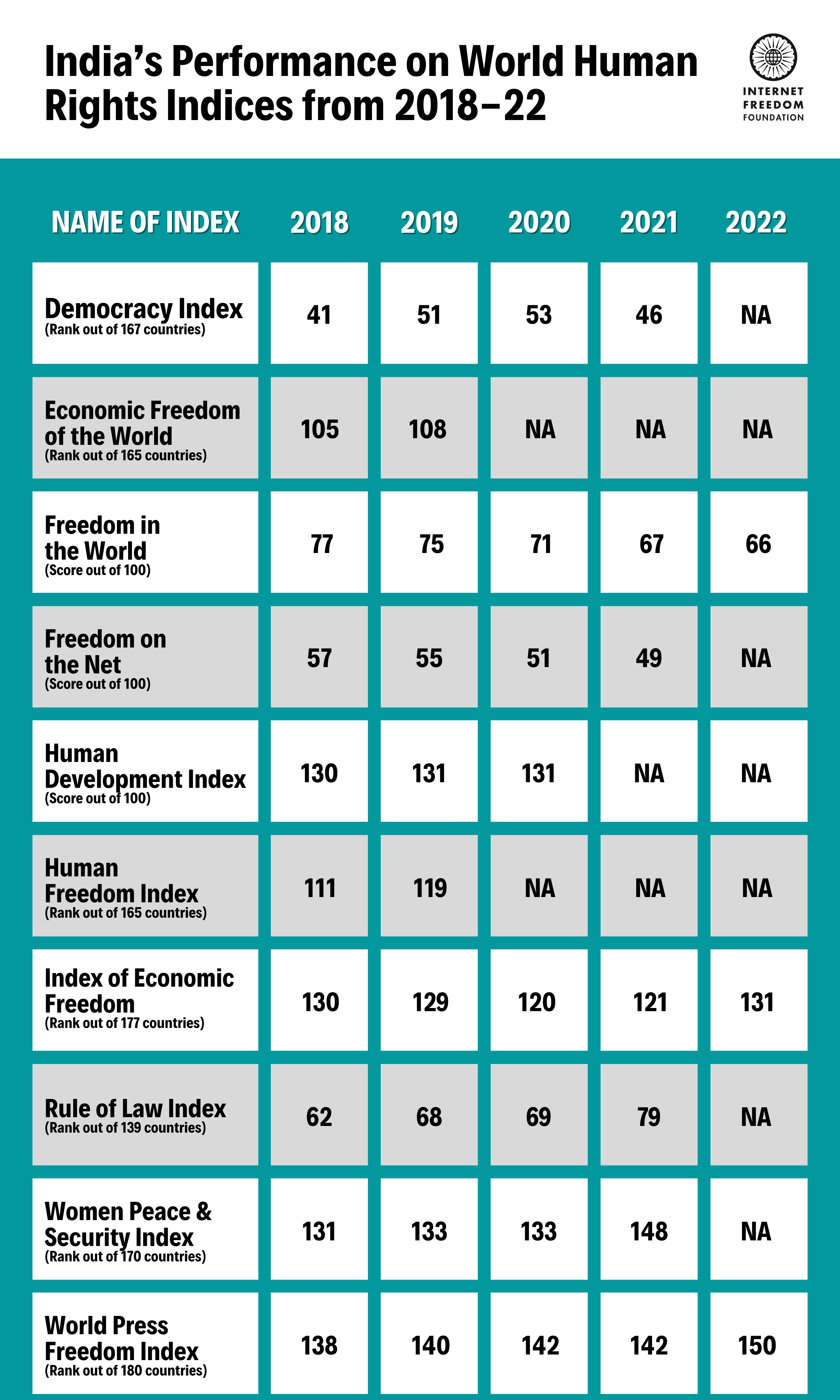

This year we celebrate 75 years of independence and with these celebrations come numerous assessments of the status of civil, political, and economic rights in the country. These assessments allow us to gauge how much we have been able to accomplish and how far we still have to go to fully achieve the ideals enshrined in our Constitution. As an organisation launched on August 15, we seek to ensure that technology respects the fundamental rights of Indian citizens and thus, on the 75th anniversary of Indian independence, we want to provide you with a brief assessment of the status of your digital rights and freedoms.

As we move towards the increasing use of technology for governance, we are becoming aware of the harms, such as bias and exclusion, that accompany these measures. For example, linking welfare schemes to Aadhaar and its biometric verification system has caused mass exclusions, and has even led to starvation deaths. Thus, it becomes imperative to ensure that social justice is the cornerstone on which we build our digital governance initiatives. The use of surveillance technology like CCTVs and facial recognition by law enforcement authorities coupled with the introduction of the Criminal Procedure (Identification) Act, 2022 also raises concerns related to 360° profiling and state sponsored mass surveillance. At this juncture, we believe that it is our responsibility to highlight these trends and raise awareness around these issues which may not affect you today but will surely affect all of us eventually.

Access to information via the internet is our fundamental right. In developing countries in particular, internet access is vital for a plethora of reasons, such as improved work productivity, better human capital development, better access to key goods and services, and reduced information asymmetries. The total number of internet/broadband subscribers in India as of May 31, 2022 is 794.68 million, which is a significant drop from the number at the end of December 2021 (829.30 million). It has witnessed a yearly growth rate of 4.29%, increasing from December 2020 (795.18 million) to December 2021 (829.30 million).

While access to the internet has grown, so have the number of executive-imposed internet shutdowns. In 2022, according to the internet shutdowns tracker maintained by the Software Freedom Law Centre, governments have already suspended internet services on 62 separate occasions, which accounts for 85% of all internet shutdowns across the world. According to Top10VPN, these 62 shutdowns have cost India 634 crores INR. The frequency with which internet is being suspended by governments, central and state, violates the direction of the the Hon’ble Supreme Court in Anuradha Bhasin vs Union of India, which held that internet suspension orders are ‘drastic measures’, and must be issued only if it is necessary and unavoidable. In the same case, the Court had also directed that internet suspension orders must be published. Yet, governments continue to suspend the internet without publishing a copy of the order. When they do publish orders, the orders do not disclose any apparent ‘threat to public safety’ or ‘public emergency’ which are prerequisites to suspend internet services as per Section 5(2) of the Telegraph Act, 1885. For example, the Government of West Bengal in March, 2022 had suspended internet services to prevent cheating in exams. In Ashlesh Biradar v. State of West Bengal, the Calcutta High Court held that the suspension was prima facie unconstitutional and directed the Government of West Bengal to restore internet services.

Another important aspect of access to the internet is the principle of net neutrality that requires internet service providers to treat all content equally without prioritising access to any one platform by creating “fast lanes” or by blocking/throttling access to others. However, while Indian authorities incorporated net neutrality within legal and licensing systems, the actual implementation of the framework remains largely non-existent. To remedy this on January 2, 2020, the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (“TRAI”) recommended the establishment of a Multi-Stakeholder Body (“MSB”), which is envisaged to play an advisory role to the Department of Telecommunications (“DoT”). However, it is unfortunate to note that the DoT is yet to act on the recommendations made by TRAI. It may be worth noting that with 5G technology being adopted in the near future, there are concerns that it will affect consumer experience and net neutrality.

The right to privacy was enshrined as a fundamental right flowing from the right to life under Art. 21 of the Constitution of India by the Hon’ble Supreme Court of India in its decision in the matter of K.S. Puttaswamy v Union of India in 2017. In the decision, Justice Chandrachud termed the formulation of a regime for data protection as a “complex exercise which needs to be undertaken by the State after a careful balancing of the requirements of privacy coupled with other values which the protection of data sub-serves together with the legitimate concerns of the State”. Since 2018, when the policy making process for data protection legislation commenced, its content and scope has gone through considerable change. After almost four years of deliberation, the Minister of Communications and Information Technology, on August 03, 2022, moved to withdraw the Data Protection Bill, 2021 in the Lok Sabha.

In the meantime, the government has not shied away from introducing framework and policies in response to the digitisation in various sectors. Most prominently, the government developed the National Digital Education Architecture (NDEAR), the Draft Health Data Management Policy, the Account Aggregator Framework and the ‘India Digital Ecosystem for Agriculture' (INDEA), for the educational, health, financial and agricultural ecosystems respectively. All of this was done in the absence of a data protection framework in India, the status of which, at the moment, remains a mystery. Further, even though the Information Technology Act, 2000 and the Information Technology (Reasonable Security Practices and Procedures and Sensitive Personal Data or Information) Rules, 2011 do attempt to regulate the collection and processing of personal data by ‘body corporates’ (private actors), these provisions have not been effectively enforced.

In the absence of any meaningful data protection, the privacy of Indian users of the internet remains vulnerable to exploitation by the private companies as well as by government authorities. For private actors such as Facebook and Instagram, what started out as methods to improve targeted advertising by convincing users to give up privacy for the sake of convenience has now become a multi-million dollar industry. On the other hand, laws pertaining to government surveillance have failed to keep up with the advancements in surveillance technology. The existing legal framework regulating government surveillance lacks meaningful oversight and caters only to targeted interception of calls & data. Here, it is essential to recognise that surveillance technology has advanced much beyond such simple interception with the advent of spyware such as Pegasus which is capable of hacking the entire device of the targeted person. However, the biggest threat to privacy is the dangerous and unregulated spread of mass surveillance technology in the country. The deployment of Close Circuit Television (CCTV) cameras is increasing rapidly in the absence of any regulating legislation, with Delhi being the most surveilled city in the world in terms of cameras per square mile. Further, artificial intelligence based technologies such as facial recognition (Visit our facial recognition systems tracker for more information), emotion recognition, and predictive policing are also being adopted increasingly by Indian law enforcement agencies, even though the use of these technologies is not regulated by any legislation.

In the absence of data protection, numerous data breaches have also put the data of Indian citizens at risk. A data breach exposes confidential, sensitive and protected information to unauthorised persons. Justice Chandrachud in the Puttaswamy decision has noted that, “(t)he right to informational privacy is not only vertical (asserted and protected against state actors) but horizontal as well. Informational privacy requires legal protection because the individual cannot be left to an unregulated market place”. Thus, data fiduciaries have a constitutional obligation to prevent infringement of the right to privacy. The economic impact of data breaches is also tremendous. According to IBM Cost of a Data Breach Report 2022, data breach average cost increased 2.6% from USD 4.24 million in 2021 to USD 4.35 million in 2022. The average data breach in India cost 17.6 crore INR in 2022. The cost increased 6.6% from last year when the average cost of a breach was 16.5 crore INR, and it is up 25% from 14 crore INR in 2020. However, the average time to identify a data breach decreased from 239 to 221 days. The average time to contain a data breach increased from 81 to 82 days.

The right to freedom of speech online is under tremendous pressure in India. According to a report by the international non-governmental organisation Human Rights Watch on the increasing criminalization of peaceful expression in India, the “government uses draconian laws such as the sedition provisions of the penal code, the criminal defamation law, and laws dealing with hate speech to silence dissent”. As a result journalists, activists, politicians, and academics have been facing criminal action for speech online. Here, it is important to remember that such actions not only affect the freedom of speech of the targeted individuals but also help in effectuating a chilling effect on others who may want to express similar sentiments but are afraid to face similar backlash.

Freedom of speech is also being curbed through the arbitrary and opaque website blocking practices of the government. Section 69A of the Information Technology Act, 2000 (IT Act) empowers the Union Government to direct intermediaries (such as internet services providers such as Airtel or platforms like Twitter) to block access to content on the internet. The Union Government has been exercising power under this provision more often than before. The number of URLs that have been blocked using this provision has grown every year since 2014 (leaving 2018). The Union Government rarely grants a hearing to originators of content and even when they do, they do not even provide a copy of blocking order by incorrectly relying on Rule 16 of the Blocking Rules. The only instance where the Union Government has provided a copy of blocking order was when the Delhi High Court, in Tanul Thakur v. Union of India, directed them to do so.

In February 2021, the MeitY notified the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021 (IT Rules, 2021), which is subordinate legislation made under Section 87 read with Section 79 of the IT Act which provides for safe-harbour immunities for intermediaries. These Rules have been criticised by experts, civil society, digital rights groups, industry bodies, technology companies, technical groups, and the media, for undermining free speech and the right to privacy as well as placing burdensome obligations upon the intermediaries, digital news platforms, and OTT platforms. The IT Rules, 2021 hence, aim to regulate a large number of online service providers constituting the sum total of digital experiences of Indian internet users. The legality of IT Rules, 2021 has been challenged by several individuals before 5 High Courts.

India can and must do better...

We find ourselves, today, at a crossroads. The increasing disregard for truly open and participative public consultation processes, the withdrawal of the data protection bill, and the imminent ominous-sounding "comprehensive legal framework" coupled with the deteriorating status of the rights to internet access, privacy, and freedom of speech & expression calls for greater attention to the erosion of digital rights in India. Whether or not we choose to mobilise resources to protect them in the long term will determine which path we ultimately take.

At this juncture, the status of digital rights in India seems grim. The fight for digital rights will be a long one. We still do not have laws which will efficiently regulate “Digital India”, even as we take big steps towards it. Public awareness around these issues is also severely lacking, which also inadvertently contributes to harm. Here, we draw inspiration from the civil rights, feminist, and environmentalist movements that have struggled for many decades to secure the victories they have today. However, no freedom is won and preserved easily, and they continue to fight for their cause.

These movements also showcase the value of fighting for small and strategic victories as the gains from such victories aggregate over time, resulting in their sustained growth. Similarly, we will continue to fight the small and big battles, whether through our public advocacy, in Courts, or before information commissioners to further our belief that each individual should be able to use technology and all that it brings with it while enjoying the benefits of our constitutional rights.

While the status of digital rights seems grim right now, we look up to civil rights & feminist movements that struggled for centuries to secure the victories they have today. Our fight too will be a long one, for which we need your support!