tl;dr

The report of the Joint Parliamentary Committee on the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 was finally tabled in Parliament on December 16, 2021. Read on to learn about the 10 key takeaways from the report on issues such as user consent, user rights, the nature of the proposed Data Protection Authority, and exemptions granted to governments.

Background

After almost two years, the report of the Joint Parliamentary Committee (‘JPC’) on the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 was finally released on December 16, 2021. The Report also contains a new version of the law titled as, “The Data Protection Bill, 2021”. This period has seen multiple consultations, a change in JPC members, and even a change in the Chairperson. For our part, we have parallelly worked on two tracks, engaging with the committee through submissions & consultations and engaging with the public through our various explainers & briefs on various aspects of the Bill.

In recent times, we have written extensively on the PDPB through:

- Our #StartFromScratch series, which was a short introduction to the Bill which included some historical and legislative context, a summary of the Bill, an overview of the issues with the Bill, and possible alternative paradigms for data protection.

- Next, through our #DataProtectionTop10 series, wherein we analysed the top 10 issues with the Bill in detail.

- Currently, through our #PrivacyOfThePeople series, which is looking at how the Bill will impact our daily lives by focusing on its impact on different sections of society

The coming days are sure to generate vociferous debate over The Data Protection Bill, 2021, and we will also be contributing to such conversations by releasing in-depth report summaries, comparisons with earlier versions of the Bill, public briefs, and issue-based analyses.

In this post, we look at ten quick key takeaways from the report.

1. Objectives become worse

One of the first noticeable changes are in the preamble of the Draft Data Protection Bill, 2021. The JPC, after arguing against the privileges of the digital economy over data protection, has decided to continue with large parts of the 2019 Bill that place economic interests (at the very least) on the same footing as the need to protect informational privacy. The Draft Data Protection Bill, 2021 undermines the primacy of an individual’s privacy by adding the words “to ensure the interest and security of the State” in the first paragraph of the Preamble. This clearly marks a primary objective of the law to serve security interests that are misplaced within a data protection law.

The report’s emphasis on promoting the digital economy through data protection legislation is also apparent with the insertion of, “that fosters sustainable growth of digital products and services” to the Preamble. This is unfortunate, since this continues the flawed approach adopted by the Expert Committee on Data Protection headed by Justice B.N. Srikrishna that prioritized economic benefits for enterprises over the protection of Indians who would be data subjects or users of digital services. Such a hierarchy is in opposition to the judgement of the Supreme Court in Justice K.S.Puttaswamy vs Union Of India (2017) (“the Right to Privacy Judgement”).

However, there is a welcome insertion of, “individual” within the text of the Preamble as the subject of protection. This provides some needed clarity in recognition that the law will serve ordinary Indians rather than artificial entities such as companies or the state. However, given the existing framing and further additions, this change will be jettisoned against objectives of profit and security.

2. Scope and name change to “Data Protection Bill”

The JPC Report has changed the name of the draft law from the “Personal Data Protection Bill”, to the “The Data Protection Bill, 2021”. This is as per the expansion in the regulatory ambit as the draft law will also regulate “non-personal data”. This follows from the definition provided by Clause 3(28), as, “data other than personal data” which is essentially data that is not identifiable with an individual. However, the principal purpose behind this framing is to provide a seemingly blank cheque to the Government under Clause 92 which states, “Nothing in this Act shall prevent the Central Government from framing (***) any policy for the digital economy, including measures for its growth, security, integrity, prevention of misuse,(***) and handling of non personal data including anonymised personal data.” Essentially, without providing any legal ingredients, or any legislative reasoning, the Central Government, in any of its ministries can formulate frameworks or policies in these subjects that may conflict or go behind the Draft Data Protection Bill, 2021.

Given that non-personal data can often be de-anonymised, or can impact individuals even when it remains in an aggregated, non-identifiable manner through digital systems we have recommended its regulation by the Data Protection Authority. Here, it becomes imperative for its regulation to be shifted from the Central Government more appropriately to the Data Protection Authority that should enjoy independence. This would also adhere to the spirit of the comments in the JPC Report that argue for it, but fail to implement it through legislative language (“1.15.8.4. The Committee, therefore, recommend that since the DPA will handle both personal and non-personal data, any further policy / legal framework on non-personal data may be made a part of the same enactment instead of any separate legislation”).

3. Consent: a torn safety net?

Any data protection law has consent as its foundational framework which is contained in Clause 11. This flows into the requirement for people to put to notice and have the choice to exercise consent. This has been made clearer by both the JPC and the Draft Data Protection Bill, 2021, which have specified that if a person exercises a choice to not provide personal data they will not be denied a service or the enjoyment of any legal right or claim. Such language could have been made clearer as in Clause 14 of the Indian Privacy Code.

At the same time, several concerning changes have been made that expand the scope of non-consensual processing of personal data. Any variation or exemption from the principle of consent must be made after the satisfaction of some qualifying conditions. The conditions where the privacy of individuals may be limited in some circumstances have been defined by the Supreme Court, they include necessity, a legitimate purpose, a proportionality evaluation and procedural safeguards as per the Right to Privacy Judgement. However, the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 in Clause 12 provides for the processing of personal data without consent when “such processing is necessary”.

Here, the Draft Data Protection Bill, 2021 not only fails to insert the additional safeguards of, “legitimate purpose” and, “proportionality” but also makes the exemption broader. It further adds, “quasi-judicial authorities” as entities that can process personal data without consent. Clause 13 also has an insertion to make non-consensual processing easier when it “can reasonably be expected by the data principal”. This undermines the principle of express consent in contexts of employment since employees will not need to be specifically notified when their personal data is processed. This is especially disappointing since the JPC, in it’s comments on clause 13, explicitly cites Article 88 of the General Data Protection Regulation, which deals with the processing of employment-related data, contains much stronger safeguards against excessive data collection by employers and calls for, “suitable and specific measures to safeguard the data subject's human dignity, legitimate interests and fundamental rights, with particular regard to the transparency of processing”.

Other vague exemptions have also been retained, as the Draft Data Protection Bill, 2021 has chosen to keep clause 14 of the 2019 Bill, which exempts user consent for data collection for purposes that range from credit scoring to the operation of search engines. The only safeguard added by the JPC was the need to ensure that such non-consensual collection of data was in the legitimate interest of the data principal, though even here this is predicated on whether it is “practiceable (sic)” to do so. At this time, we may also point out that the JPC Report and the Draft Data Protection Bill, 2021 contain grammar and spelling errors that require correction.

4. Weakened user rights

The Draft Data Protection Bill, 2021, following earlier versions of the PDPB, provides users with certain rights such as the right to confirmation and access (Clause 17), the right to correction and erasure (Clause 18), the right to data portability (Clause 19), and the right to be forgotten (Clause 20). The first noticeable change is the expansion of Clause 17 with the insertion of sub-clause 4 to include rights that can be exercised in the event of the demise of the data principle primarily for the intended objective of the nomination of legal heirs and representatives. This is a welcome addition but it does not square with several other provisions that continue to undermine user rights from prior versions of the Data Protection Bill.

For example, the Draft Data Protection Bill, 2021 has retained Clause 18(2) of the 2019 Bill, which allowed data fiduciaries to reject requests for correction, completion, updation or erasure of personal data if they disagreed with such requests (on the basis that certain data is still necessary for the purpose for which it was processed). Additionally, Clause 19 limits the purpose of data portability which is incredibly important for mitigating harms by big tech. This is through the insertion of vague language in Clause 19(2) of the Draft Data Protection Bill, 2021 as a result of which, requests for data portability may be refused by Data Fiduciaries due to technical infeasibility. Further, such refusal will be specified in future by regulations.

The treatment of the right to be forgotten provision is also of interest as there is noticeable change in Clause 20(2) which provides an exemption from its application for, “the right of the data fiduciary to retain, use and process such data”. This makes little sense as data principals (people) have legal rights and the data fiduciaries (an artificial entity) that process their data have duties and responsibilities under the law. Beyond this logical error, the consequence of such change is that it increases the discretion of government departments and companies to hold on to personal data. The JPC Report, while acknowledging harms that will result under Clause 21 from the charging of fees to exercise user rights, chooses to retain this provision. In some marginal relief, the Draft Data Protection Bill, 2021 inserts a proviso that specifies that any charges that are levied by Data Fiduciaries will be subject to regulations formulated by the Data Protection Authority.

One welcome change is within Clause 62 which provides for the ability of ordinary citizens who are data subjects to avail remedies by filing a complaint with the Data Protection Authority. This Clause also provides for compensation.

5. Social Media and Intermediary Liability

Scrutiny of social media platforms has been a primary topic of consideration in technology policy with the revelations of the Facebook Files. This has impacted the JPC Report with several fresh insertions in the Draft Data Protection Bill, 2021. At the outset, we would like to point out that, while data protection laws are important instruments to regulate the flow of data to big technology platforms, they by themselves are distinct from broader social media regulation that deserves an independent statute (eg. UK’s Online Harms Whitepaper). Here the JPC Report states that, “social media platforms have been designated as intermediaries in the IT Act and the Act had not been able to regulate social media platforms adequately” (Para 1.15.12.7) and also (correctly) that, “the present bill is about protection of personal data and social media regulation is altogether a different aspect which needs a detailed deliberation” (Para 2.126 at Page 99). However, despite these observations, it goes on to recommend significant changes to social media regulation.

The JPC Report has noticed and commented on several problems with social media that range from, “the prevalence of fake accounts”; “instigated people across the globe to plan, organise and execute revolutions, protests, riots and spread violence”. Based on these concerns the JPC Report recommends the following changes:

- Publishers : “The foremost point of concern for the Committee was that the IT Act had designated social media platforms as 'intermediaries'. In this regard, the Committee were of the view that the social media platforms may not be designated as such because, in effect, they act as publishers of content, whereby, they have the ability to select the receiver of the content, as well as control the access to any content posted on their platform.” (Para 1.15.12.4.)

- Verification : “A mechanism may be devised in which social media platforms, which do not act as intermediaries, will be held responsible for the content from unverified accounts on their platforms. Once [an] (sic) application for verification is submitted with necessary documents, the social media intermediaries must mandatorily verify the account.” (Para 1.15.12.7.)

- Local Offices : “Moreover, the Committee also recommend[s] (sic) that no social media platform should be allowed to operate in India unless the parent company handling the technology sets up an office in India.” (Para 1.15.12.7.)

- Social Media Regulatory Body : “Further, the Committee recommend[s] (sic) that a statutory media regulatory authority, on the lines of Press Council of India, may be setup for the regulation of the contents on all such media platforms irrespective of the platform where their content is published, whether online, print or otherwise.” (Para 1.15.12.7.)

Flowing from these recommendations there are significant changes in the Draft Data Protection Bill, 2021 with the preamble changing the phrase, “social media intermediaries” to “social media platforms”. This corresponds with the insertion of a fairly vague definition of, “social media platforms” under Clause 3(44) that now reads as, “social media platform” means a platform which primarily or solely enables online interaction between two or more users and allows them to create, upload, share, disseminate, modify or access information using its services”.

The principal regulations on “social media platforms” have been made with significant changes to Clause 26 which determines a “significant data fiduciary”. Here, for a social media platform to be a significant data fiduciary Clause 26(1)(f) provides for threshold limits of user numbers that are notified by the Data Protection Authority or, “significant impact on the sovereignty and integrity of India, electoral democracy, security of the State or public order…”. This classification permits further regulatory compliance such as, a data impact assessment under Clause 27; mandatory registration with the Data Protection Authority under Clause 28(3); the appointment of a data protection officer, or increases the powers of oversight of the Data Protection Authority under Clause 30.

While these may be welcome additions, they are offset by the process of verification of social media users. This undermines the principle of data minimisation as it would increase personal data held by social media platforms and increase surveillance of users by tying their online profiles to their real-world identities. Such social media intermediaries, as per Clauses 28(3) and 28(4) of the Bill, would have to enable users to “voluntarily verify their accounts in such manner as may be prescribed”, after which verified accounts may be identified with some visible mark. We fear such a provision even though it is premised on choice, as such choice when offered by social media platforms may become mandatory or the norm through practice and future regulations. Verification of accounts will also adversely affect minorities, whistleblowers and victims of sexual assault, who often resort to anonymous identities on social media websites to share their experiences. Such a provision is not found in any data protection law globally and is a deviation from established privacy norms as it can increase the risk from data breaches and entrench more power in the hands of large players who can afford to build and maintain such verification systems.

While the Draft Data Protection Bill, 2021 does not make any provisions to treat platforms as publishers, the JPC Report itself makes recommendations for a regulatory framework premised on such an understanding. We believe this is flawed and social media companies do not fall within a clear binary of, “passive intermediaries” completely exempt from legal compliance, nor, “publishers” that are liable for user-generated content, for the purposes of some specific harms that require independent and detailed study. Here, we contest the assertions of the JPC Report as it undermines well-established principles of intermediary liability that promote free speech and expression as noted by the Supreme Court in Shreya Singhal v. Union of India.

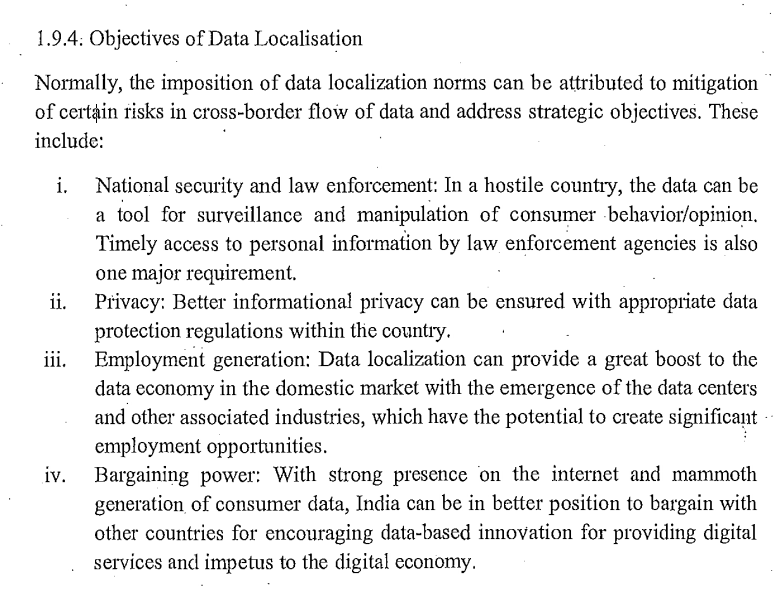

6. The burden of data localisation

The JPC Report devotes an entire section titled the, “growing importance of data localisation”. As we have explained, data localisation while strengthening state control does not serve constitutional objectives, resulting in negative impacts on innovation and digital rights.

This also becomes clear from the JPC Report which lists the following objectives from data localisation that are pasted below.

Here the JPC Report in addition to retaining Clauses 33 and 34 with respect to data localisation also calls on the Central Government to, “prepare and pronounce an extensive policy on data localisation”. The significant changes are in Clause 34 of the Draft Data Protection Bill, 2021 which expand the grounds under which transfers of sensitive and critical personal data can be prohibited when, “... the object of such transfer is against public policy or State policy”. Despite a proviso to the Clause, the phrases, “public policy” and “state policy” are left undefined and these may result in vagueness and unguided discretion for enforcement by the Data Protection Authority.

Here, there is a noticeable reduction in the autonomy of the regulatory body i.e., the Data Protection Authority to permit transfers of sensitive personal data. Fresh language has been inserted in various sub-clauses to exercise such power, “in consultation with the Central Government”. This change is not isolated and is repeatedly mentioned by way of fresh insertions throughout the Draft Data Protection Bill, 2021 which increases government power over the Data Protection Authority thereby reducing its independence. Practically, this would allow a policy pronouncement by the Ministry of Electronics and IT (MEITY) to override protections under the Draft Data Protection Bill, 2021.

7. Government exemptions become easier

The Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 was intensely critiqued for providing large exemptions to Government from compliance under the law. However, the Draft Data Protection Bill, 2021 marks a worrying progression and makes it easier for the government to completely evade the jurisdiction of a data protection law. This becomes evident as the JPC Report quotes directly from Justice B.N. Srikrishna Report (Paras 2.166-2.168 at Page 118).

Here, the Draft Data Protection Bill, 2021 cements the exemption for Government Departments by the insertion of a non-obstante provision in Clause 35 which reads as, “Notwithstanding anything contained in any law for the time being in force…”. At the same time while Explanation (iii) to Clause 35 does contain a reference to safeguards that should be as per a “just, fair, reasonable and proportionate procedure”. It is important to note that such protection is limited since it applies only as a procedural safeguard and not as a condition to exercising the grounds of exemption. The grounds under which an order for exemption may be issued remain concerning as the standards for it are, “necessary” or, “expedient”. As per a dictionary definition of, “expedient” it is defined as, “helpful or useful in a particular situation, but sometimes not morally acceptable”.

Many technology policy professionals and lawyers are well aware that the Draft Data Protection Bill, 2021 unlike the Privacy Code, does not regulate surveillance. Hence, the Draft Data Protection Bill, 2021 exemptions apply only to conditions under which data was being gathered with consent and notice by government departments. It is important to restate that this exemption stands above and beyond cases of interception and mass surveillance technologies such as facial recognition that are not even being regulated by any pending legislative proposal by the Central Government including the Draft Data Protection Bill, 2021.

8. A DPA subordinate to the Central Government?

The enforcement of data protection and a realisation of the rights will depend on an independent, autonomous and well resourced regulatory body, i.e. the Data Protection Authority. However, the appointment and powers of the Data Protection Authority have several concerning design choices that give power and control over it to the Central Government.

As per Clause 42 of the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019, the Selection Committee for appointing the members of the Data Protection Authority would comprise entirely of members of the executive. This clause may imply a Data Protection Authority will be beholden to the Central Government. While changes have been made in Clause 42(2) the Draft Data Protection Bill, 2021 by which the Attorney General, an independent expert, a director of an IIT, and a director of an IIM is included in the selection panel this change does not address the underlying problem. This is because all such appointments are also made and serve at the pleasure of the Central Government and further choice extends in picking any one director from the multiple IITs and IIMs across India.

Further, Clause 86 of the 2019 Bill stated that the Data Protection Authority shall be bound by the orders of the Central Government "on questions of policy". Here, the JPC Report has recommended the removal of the term, “on question of policy” and said that “ the Authority should be bound by the directions of the Central Government under all cases and not just on questions of policy” (para 2.266 on pg 160). As a result, the decision of the Central government will now be final in all matters, further weakening the independence of the Data Protection Authority which has now been rechristened under Clause 87 of the Draft Data Protection Bill, 2021. There is also a noticeable expansion in Clause 94 in which the power of the Central Government has been expanded to include various fresh subjects.

9. Data Breaches and Security Researchers

Data breaches are becoming increasingly prevalent in modern India. In 2021, as of November, a study by cybersecurity company Surfshark reported that 86.63 million Indian users had been breached. An IBM study also reported the average data breach in India cost 16.5 crores INR, an increase of 17.85% from 2020.

In such a context, it is unfortunate to note that breach reporting and disclosure mechanisms have not been adequately dealt with in the JPC Report. As per Clause 25 of the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019, there is no provision for the protection of whistleblowers who report a data breach, which only provides for a data fiduciary to report breaches to the DPA in cases “where such breach is likely to cause harm to any data principal”. Now, the Draft Data Protection Bill, 2021 recommended by the JPC does remove the discretion earlier granted to the data fiduciaries by removing the phrase “likely to cause harm to the data principal”. Further, the Bill also specifies a definite timeline for reporting a breach: Clause 25(3) states that data fiduciaries must notify the Data Protection Authority “within seventy-two hours of becoming aware of such breach”. However, the decision to notify data principals about a breach of their data is still vested with the Data Protection Authority, which will take into account the severity of the harm before notifying the data principal of the breach.

Additionally, it is also important that India’s data protection legislation set forth an institutionalised mechanism for cybersecurity personnel to safely and freely, without any fear of retaliation, report such breaches. While Clause 38 of the 2019 Bill allowed the Data Protection Authority to, “exempt such class of research, archiving, or statistical purposes from the application of any of the provisions of this Act as may be specified by regulations”, it does not carve out any such exceptions for skilled cyber security researchers who conduct vulnerability testing and are often subjected to harassment by vexatious legal claims and proceedings. Unfortunately, the Draft Data Protection Bill, 2021 does not address this issue at all, retaining Clause 38 from the 2019 Bill and leaving open the prospect of vulnerability testers being harassed by frivolous legal claims. That the existing regulatory regime may be hostile to cybersecurity researchers has effectively been accepted by the Indian Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT-IN) which, in response to recent representation by us, stated that the ‘Responsible Vulnerability Disclosure and Coordination Policy’ notified by CERT-IN was more akin to a ‘disclaimer’ and that any regulatory changes would need to be taken up by the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology.

10. Some other concerning provisions

The Draft Data Protection Bill, 2021 does not acknowledge a natural person as the owner of their data. Rather, the JPC Report refers to data as the “new oil”, “asset of national importance which is waiting to be tapped...”, and “the fuel for a new economy...”, (in paras 1.1, 1.2.10, and 1.4.1 respectively). Evidently, the report views data as a valuable resource, the full potential of which remains to be unlocked. This can also be witnessed from the retention of clause 40 from the 2019 Bill, which allowed the setting up of ‘innovation sandboxes’ that would seemingly operate under a liberalised data protection regime. Indeed, Clause 40 of the Draft Bill explicitly states that the Data Protection Authority may permit “certain regulatory relaxations for a specified period of time” for these sandboxes. This is unfortunate since regulatory sandboxes have been criticized for their use as an avenue to avoid compliance burdens. Consumer groups have raised questions about regulatory sandboxes, including the lack of public and consumer input, exemptions from liability for unfair or deceptive practices, and the lack of protection for consumers and users.

The Draft Data Protection Bill, 2021 also doesn’t deal with data collected prior to the Bill coming into force. While the JPC Report does recommend “an 27 approximate period of 24 months may be provided for implementation of any and all the provisions of the Act so that the data fiduciaries and data processors have enough time to make the necessary changes to their policies, infrastructure, processes etc” (Recommendation no. 3 on page 28), it does not deal with data collected prior to the bill coming into force, how such data processing will be affected by the enactment of this bill, and what measures must be taken to bring such processing in conformity with the provisions of the bill, especially in cases wherein consent has been collected in a manner inconsistent to the provisions of the Bill This can be contrasted with the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which repealed the EU’s pre-existing Directive 95/46/EC popularly known as the Data Protection Directive. Recital 171 of GDPR also provided that processing already underway under the earlier Directive be brought into conformity with GDPR within two years after which this Regulation enters into force.

This post is just our initial response to the JPC on the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019. In the coming days, we will be releasing in-depth report summaries, comparisons with earlier versions of the Bill, public briefs, and issue-based analyses, so stay tuned!