tl;dr

Voice-enabled AI assistants like Alexa, Google Assistant and Siri reside not only on our smartphones but also in millions of bedrooms. The intimacy they enjoy presents a range of privacy risks that can be mitigated by a user-centric, rights focussed, data protection law. In this #PrivacyOfThePeople series, we discuss concerns on consent (when and how are such devices collecting data), data retention (storage of parts of audio recordings for undefined periods), cyber security audits (malicious attacks), and data sharing and surveillance (exposure of voice recordings to Voice Assistance training personnel and law enforcement).

Background

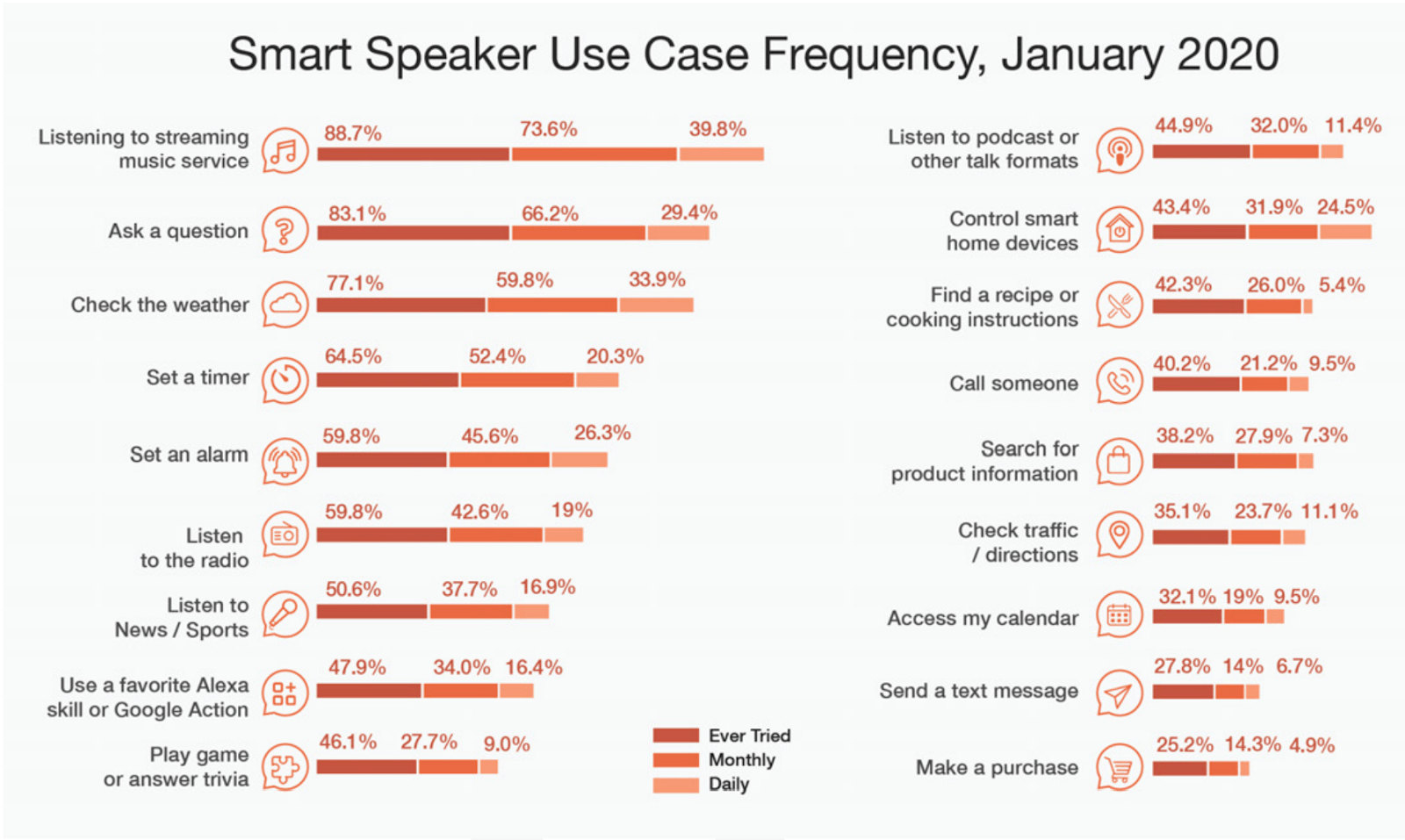

India is witnessing a 270% year-on-year growth in voice searches. In 2020, 60% of users in India were estimated to be interacting with voice assistants (‘VA’) on their smartphones. The Mobile Marketing Association in its ‘The Voice Playbook’ (2021) records that smart speakers are being used on a daily basis for listening to music, asking questions, checking the weather, setting a timer, setting an alarm, listening to news and so on. The report points out that the reason for such exponential growth may be convenience (voice is faster than typing) and lack of literacy in India which prompts the rural population to use VAs.

Mark Weiser who headed Xerox PARC labs explained it well when he stated that, “The most profound technologies are those that disappear. They weave themselves into the fabric of everyday life until they are indistinguishable from it.” Given the ubiquity of AI assistants in our daily interactions, we analyse the privacy and security concerns on three predominant, popular deployments, Alexa, Google Assistant, Siri. The basis of this analysis is the Draft Data Protection Bill, 2021 or how an ideal data protection framework can regulate their use, while maintaining innovation and limiting harm.

Privacy concerns on consent and retention

The first privacy concern is regarding data retention. All three VAs store a part of user data including audio recordings for an undefined period even when retention of data indefinitely is against the internationally accepted principle of storage limitation. Their data retention practices are detailed below:

- Alexa: The data collected is associated with Amazon accounts. Amazon stores recordings by default unless users choose to delete them. They can opt-in for auto-deletion of recordings that are older than “3 or 18 months” or choose to not save records at all. Do remember though, that the recordings are still processed on the cloud servers before deletion. Also, the policy is not clear on what happens to the recordings which do not meet this cut-off. Moreover, deletion only applies to voice recordings and Amazon may “retain other records of your Alexa interactions”. Amazon has also previously admitted to holding on to data received through Alexa voice interactions despite user-deletion requests. Further, as per the policy, the actions Alexa took in response to your requests can be stored for an undefined period. That means if Alexa repeated any personally identifiable sensitive information for a user, it will be on the cloud server for as long as Amazon wants it.

- Google Assistant: The voice data collected through Google Assistant is associated with Google accounts. Voice recordings are not stored by default and users have an option to delete them. However, if users consent to share their recordings for the purpose of improvement of features, snippets of such recordings (after being dissociated with users’ accounts) can be saved for an undefined period to improve machine learning. Google’s policy is unclear on retention of other kinds of Google Assistant-related data, but Google’s privacy policy does allow for data retention.

- Siri: A users’ ‘request history’ generated as a result of using Siri is associated with a random-device-generated unique identifier and not with an Apple ID or email address. Request history includes transcripts, audio for users who have opted in to Improve Siri, Siri Data i.e., contact names, names of apps installed on the device, music etc., device specifications, approximate location etc. Voice recordings are saved on Apple’s servers only if one opts in on the ‘Improve Siri’ feature. Otherwise, there is an option of processing user-voice on the device itself. However, irrespective of this option, the transcripts of interactions are always sent to Apple to process requests. The ‘request history’ is disassociated from the unique identifier after 6 months of its creation, but can be stored for up to 2 years on Apple’s servers to help Apple improve its services. In fact, a small ‘subset’ of these requests may be stored for an undefined period. Users do have an option to ‘request’ deletion of request history (the pop-up states that the data ‘will’ be deleted), but it is not automatic.

The second privacy concern is the processing and storage of data without user knowledge and consent. VAs work based on users' voices - it is their main feature. All the above-mentioned VAs activate upon hearing a particular activation keyword. Although some of the policies claim that the cloud servers do not store data/voice unless the activation word is detected, there is constant exchange of voice & related data between their cloud servers and the VA device. This is especially concerning in cases of false activation when data may be getting stored without actual knowledge. The process of activation followed for each VA is detailed below:

- Alexa: Alexa devices are ordinarily activated by voice on hearing the ‘wake word’ chosen by a user (e.g., Alexa, Amazon, Computer or Echo). Amazon claims that till the wake word is detected, no audio is stored or sent to the cloud. The question here is, how is the wake word detected? While that is not answered clearly in the policy, Amazon has described how it verifies a wake word. As per its policy, the Alexa-enabled device starts streaming audio to the cloud upon detection of the wake word. This is where Alexa performs a “cloud verification” to confirm its detection. If the cloud verification does not also detect the wake word, Alexa stops processing the audio and ends the audio stream to the cloud. If the wake word is detected, Alexa attempts to determine when a users’ request ends and stops the audio stream at that point. Interestingly, the policy is silent on what happens to the audio received if the wake word is not verified or incorrectly verified by Alexa.

- Google Assistant: As per Google’s policy, the device is on standby mode by default and only activates upon hearing words like “Hey Google” or “Ok Google.” Short snippets of audio (a few seconds) are processed to detect an activation. If no activation is detected, then those audio snippets won’t be sent or saved to Google. If an activation is detected, the Assistant comes out of standby mode to fulfil user requests. The policy is again unclear on how the activation word is detected and where the short snippets are processed. If snippets are processed on Google’s server, the policy must mention how Google deals with the data associated with those snippets.

- Siri: It can be activated by voice by using the words, “Hey Siri.” Siri’s policy is completely silent on how it processes the activation word. However, Siri has a peculiar feature. Siri Settings of a device clearly states if a user’s voice is processed on their device. If the same is not stated, the voice inputs are sent to and processed on Siri servers. Therefore, if the voice is being processed on the device itself, the issue of processing and storage of data without a user’s knowledge may not be that exacerbated because the device is always with the user. The policy also states that transcripts of voice recordings are always sent to Apple servers. Therefore, in cases of false detection of the activation word, even if the audio is processed on the device, processing and storage of transcripts on servers will still take place without user knowledge.

Common concerns associated with VAs

The common concerns associated with all VAs independent of their policies are surveillance and security. Human involvement is essential for improvement of Natural Language Processing (allows interaction with a system in a spontaneous way) and machine learning. Employees of Apple, Google and Amazon review randomly selected parts of voice recordings to verify whether VAs processed the voice requests correctly. Training personnels also listen to the audio, transcribe it, annotate it, and convert it into material that can be used for training voice recognition algorithms. So, even when the voice snippet stored in cloud servers is not associated with an identifier on Siri, or an ID on Google Assist, if the snippet is (say) of your partner saying, “order Raj his favourite Margherita at our Lonavala house”, the training personnel hearing this information will know personally identifiable information about Raj and the speaker. Another risk of exposure is when governments, law enforcement authorities or courts demand audio recordings and associated data for the purpose of investigations.

Security concerns are associated with malware attacks and hacking. Researchers have found that successful malicious attacks against VAs are becoming more and more sophisticated. The hyperlinked study summarises flaws that allow remote execution of voice commands on Alexa which can enable a malicious user to make online purchases with another user’s VA, discusses security attacks such as ‘phoneme morphing’ in which a VA is tricked into thinking a modified recording of an attacker’s voice is the device’s registered user, and ‘dolphin attack’ in which inaudible voice commands can be used to communicate with VAs, evading detection by human hearing. These attacks allow the extraction of personally identifiable information from unsecured VAs with ease. Therefore, the privacy of voice recordings depends heavily on the security of the servers on which they are stored, and the devices on which they are enabled.

The Data Protection Bill, 2021 and VAs

After two years of its constitution the Joint Parliamentary Committee (“JPC”) on the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 released its report in December 2021. The report introduces Data Protection Bill, 2021 (“Bill’) incorporating the amendments and omissions suggested by the JPC.

Clause 17 provides users with the right to confirmation and access. This right will allow VA users to demand confirmation from the data fiduciaries on whether their request to delete their data has been processed. Notwithstanding the policies of the data fiduciaries, by virtue of Clause 18, a VA user can also demand erasure of personal data which is no longer necessary for the purpose for which it was processed.

As seen above, when VA users consent to the use of audio recordings by Amazon, Apple, and Google for improvement of services, the companies can store small anonymised snippets or subsets of the voice recordings for an undefined period. Clause 20 applies when a user wants to withdraw such consent. Upon withdrawal of consent, it gives the user the right to restrict or prevent processing of their personal data (i.e. one’s voice) by a data fiduciary (provided it does not take away the data fiduciaries rights under this Bill.)

Pursuant to Clause 50, the Data Protection Authority must specify a specific code of practice for VAs. The European Data Protection Board has adopted guidelines on virtual voice assistants (‘VVA’) which can be used as a guiding document. The guidelines bring all forms of interaction with a VVA under the scope of personal data. Further, since VAs are associated with large size of personal data, the guidelines in addition to adopting the data storage limitation (store only as long as it is necessary to store for purposes for which it is processed) and data minimization principles (limitation of type and quantity of data), have also suggested that data retention periods should be tied to different processing purposes.

The Recommendations

What is seen last, is remembered best: so here is a shortlist of recommendations on what can be done to protect user privacy and security while using VAs -

- Right to privacy: Even in the absence of a data protection law, users have a fundamental right to privacy which can only be violated if the three-prong test of legality, necessity and proportionality stands fulfilled. This must be kept in mind by data fiduciaries while dealing with personal data. Hence, all companies implementing voice assistants need to closely conduct internal privacy reviews periodically drawing best practices on data protection.

- Code of Practice: Specifically, when a data protection law is made a specific code of practice for voice assistants in line with best international practices must be specified by the Data Protection Authority under Clause 50 of the Bill.

- Data retention: Given the unique identifying nature of a voice, existing data retention practices should be amended to adopt a higher threshold for justification of data retention practices with respect to personal data associated with VAs.

Important Documents

- The report of the Joint Parliamentary Committee on the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 tabled on December 16, 2021 (link)

- Key Takeaways: The Joint Parliamentary Committee Report and the Data Protection Bill, 2021 #SaveOurPrivacy (link)

- Comparing the Data Protection Bill, 2021 with its predecessors (link)

- Our #PrivacyOfThePeople series, where we have discussed the impact of the PDPB on different sections of society (link)