tl;dr

In the latest post in our #PrivacyOfThePeople series, we look at the impact of the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 on digital lending application users. We examine both illegal and ‘legal’ lending apps and look at how the data protection bill will impact digital lending.

Background

Through our #PrivacyOfThePeople series, we aim to explore the ways in which the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 affects the lives of various segments of society. To date, we have explored the effects of the Bill on gig and app-based workers, ASHA and Anganwadi workers, farmers, social media users, medical patients, students, and dating app users.

This week, we look at digital lending apps that purportedly aim to serve consumers who have been excluded from the formal financial system and thus, increase financial inclusion. We look at both illegal lending apps - which are clearly predatory and can lead to devastating consequences for the most vulnerable - and ‘legal’ lending apps. While there’s no clear demarcation between illegal and ‘legal’ lending apps as digital lending is unregulated; legitimate lending apps tend to be backed by NBFCs or banks which fund loans, follow fair practice guidelines issued by the RBI, and do not charge unreasonable interest rates. However, the volume of non-financial personal information collected by these ‘legal’ apps, combined with lack of regulation or a personal data protection bill can result in credit discrimination, security breaches and opaque lending practices. We also look at how the proposed Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 will address these issues.

The issue

After the COVID induced lockdown, a slew of illegal digital lending apps started offering unsecured loans to desperate borrowers at exorbitant interest rates ranging from 60% to 100% with extremely short tenures of 7 to 15 days without any KYC or credit score verification. These apps also required extensive permissions to access the borrower’s phone for collecting contact information, photos, text messages, location and even battery percentage. The entire process was online and required no in-person verification. However, once the borrowers defaulted, the representatives of these apps started harassing borrowers by sending abusive messages, publicly shaming them by sending messages to their friends and relatives, and in some instances demanding that the borrower send them naked images. This has pushed at least 11 people towards suicide since November 2020.

Various police investigations have been initiated, and Google has reportedly removed around 100 lending apps from the Google Play Store. These stories have also caught the attention of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), which in January 2021, set up a six-member working group to regulate digital lending through mobile apps.

This is not the first time FinTech based microfinance services has led to delinquencies and repayment crises. In Assam, for example, the withdrawal of formal credit led to a rise in micro-finance borrowings. Largely unregulated, reckless borrowing combined with exorbitant rates of interest has led to a debt crisis among small landholders, leading to an increase in suicides.

Illegal and predatory lending apps have led to devastating consequences for the most vulnerable, and all necessary steps must be taken to prohibit these apps and bring the perpetrators to justice.

However, things in the ‘legal’ digital lending industry aren’t all hunky-dory either.

Digital lending apps fill a genuine market gap by offering credit to poor and underserved borrowers who have traditionally been left out by mainstream financial institutions as they lack formal credit history and banks deem them unprofitable to lend to. But while digital lending has the potential to increase financial inclusion, in a country with low levels of digital literacy, it may come at the expense of privacy and consumer welfare. Further, simply using new technologies without addressing the underlying structural reasons for this credit gap would not only fail to solve this problem but also potentially aggravate it. In the last few years, the non-performing asset ratio for Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) has been on a rise due to the gradual decline of bank credit to MSMEs and the increasing access to fintech based micro-finance. This is one of the drawbacks of Fintech, as it provides some credit relief in the short term, but in the long term, it begins to affect the operations of regular banks, which can lead to the closing of branches of banks, and consequently increase account closures. This can exacerbate the very issues these technologies propose to solve.

App-based digital lenders have been in business for a long time, many of them are either registered as NBFCs or have arrangements with banks or NBFCs, and mostly play the role of connecting borrowers with institutional lenders. They offer credit assessment, credit scoring services, and other user-facing services, while the actual loan is funded by institutional lenders.

These digital lenders assess the creditworthiness of borrowers using Artificial Intelligence (AI) algorithms that rely on “alternative sources of evaluating creditworthiness” such as text messages, location, online and social media activity, expenditure and consumption patterns of users etc. This information (non-financial personal information) serves as a proxy for financial information (credit score, financial history etc.) which is more commonly used to assess creditworthiness.

Using personal information for making lending decisions can lead to negative outcomes due to the following issues:

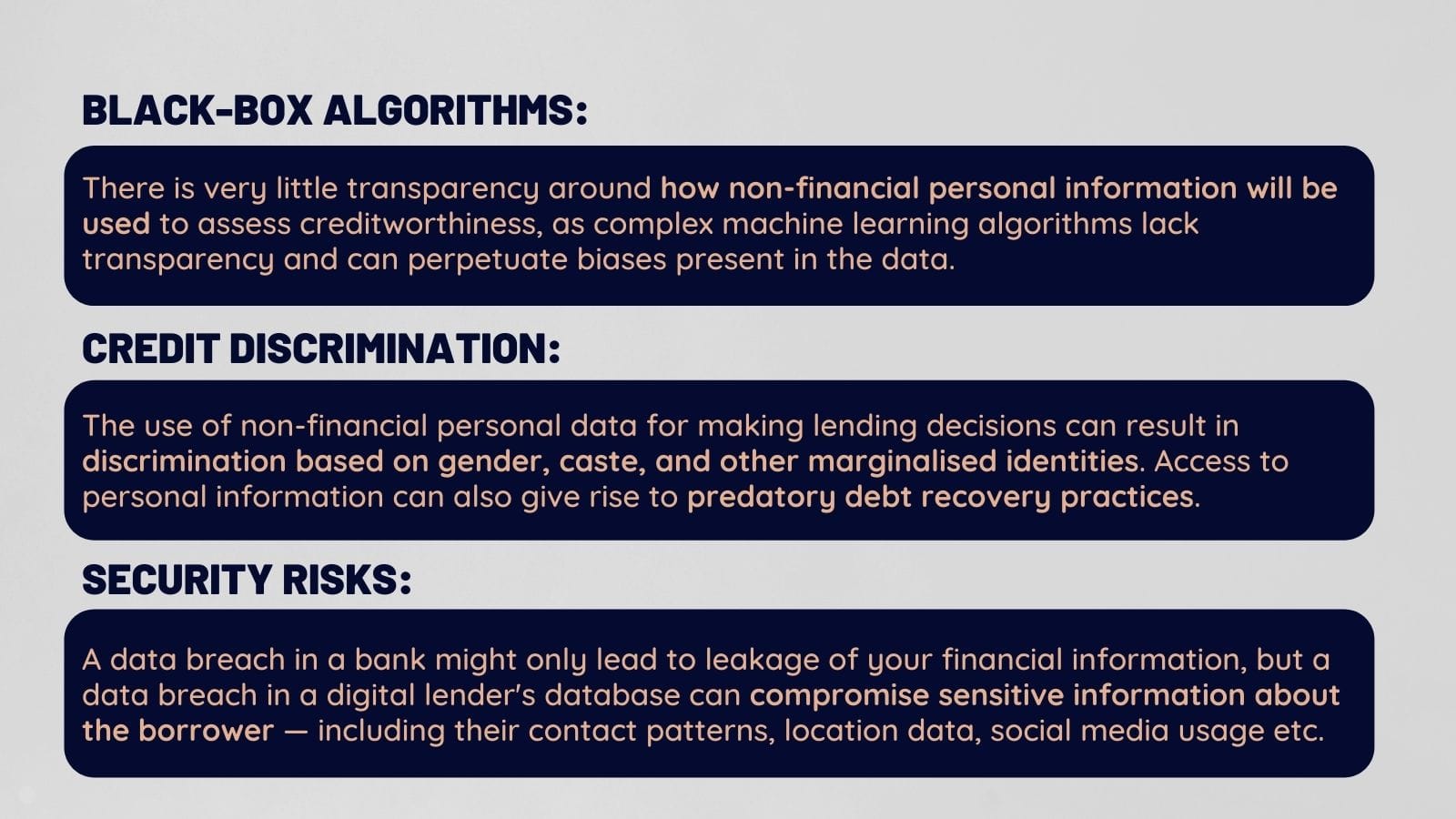

- Black-Box Algorithms: There is very little transparency as to how this non-financial personal information will be used to assess creditworthiness as complex machine learning algorithms lack transparency and can perpetuate biases present in the data, and often there is no way to detect such biases. Without a legal obligation to explain the lending decision, especially when the loan is denied, the entire process becomes even more opaque.

- Credit Discrimination: Another major concern is that the use of non-financial personal data for making lending decisions can result in discrimination based on gender, caste or any other group membership. Data gathered from digital trails such as location, contact history etc. can correlate with group membership. In a residentially segregated country such as India, people belonging to a certain caste or religion might reside in specific neighbourhoods and visit specific areas, not frequented by people from other castes or religions. Basing lending decisions on personal information can perpetuate discrimination, especially among the most marginalized. Also, access to personal information can give rise to predatory debt recovery practices as lenders can use the borrowers' contact information to contact their friends and relatives.

- Security Risks: The collection of massive amounts of personal information, combined with the lack of regulation can also have profound implications for data privacy. A data breach in a bank might only lead to leakage of one’s financial information, but a data breach in a digital lenders database can compromise sensitive information about the borrower including their contact patterns, location data, online and social media usage data etc. In the absence of the PDP bill, these lenders are under no obligation to report such data breaches.

The PDP Bill

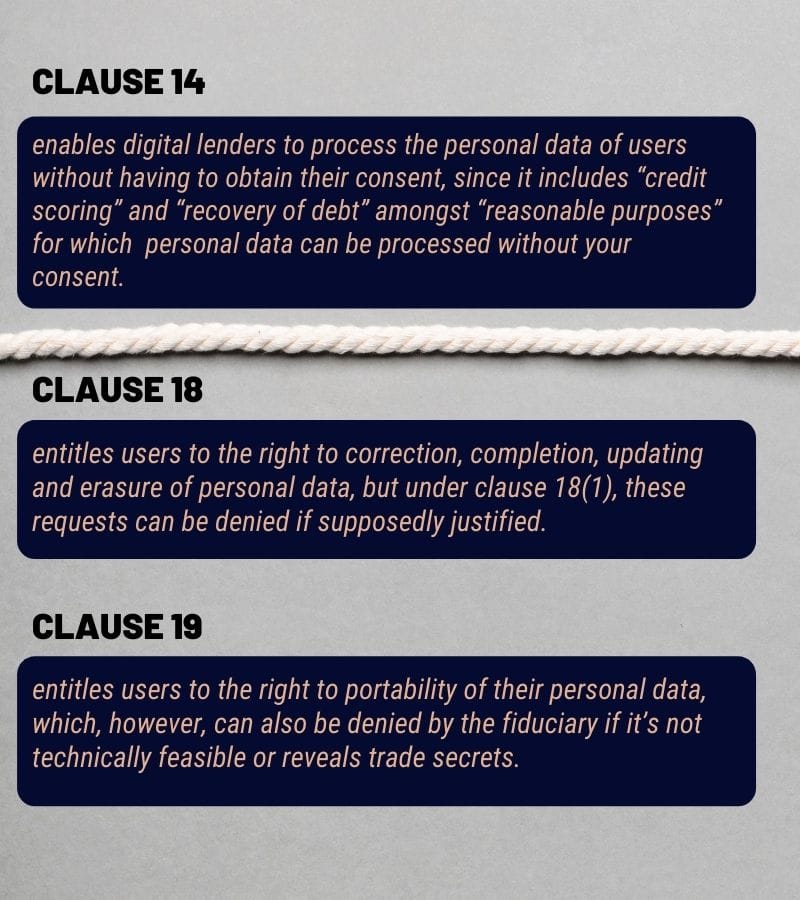

Clause 14 of the Personal Data Protection Bill will essentially enable digital lenders to process the personal data of users without having to obtain their consent. The said clause includes “credit scoring” and “recovery of debt” amongst “reasonable purposes” for which personal data can be processed without obtaining the consent of the data principal. This exemption is overbroad, vague and undermines the privacy of users.

Further, the PDP bill provides limited and conditional rights to users. Clause 18 of the PDP bill entitles users to the right to correction, completion, updating and erasure of personal data, but under clause 18(1), the data fiduciary can reject such user requests after providing a justification. Clause 19 of the PDP bill entitles users to the right to portability of their personal data, which, however, can also be denied by the fiduciary if it’s not technically feasible or reveals trade secrets. Further, clause 21 enables data fiduciaries to charge a fee for complying with the above-mentioned user requests. Therefore, if a borrower requests the lender to erase their personal information, the lender can refuse to do so and can keep utilising user data to increase the accuracy of their prediction algorithms. Even if the lender agrees to erase such data, they are entitled to charge a fee from the user for doing so.

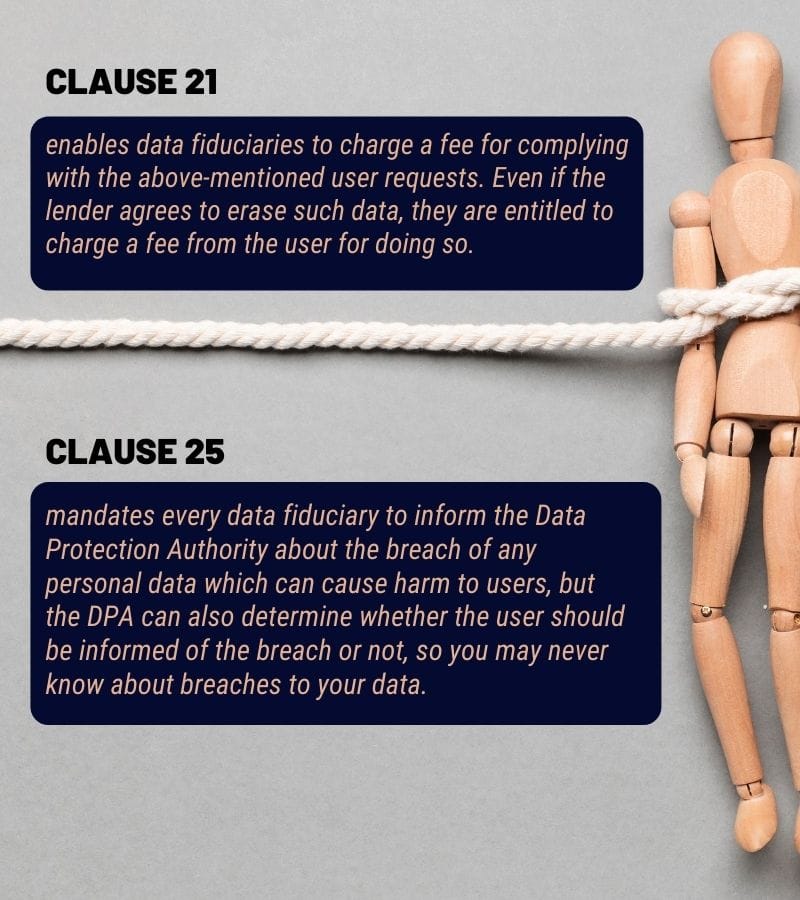

Clause 25 of the PDP bill mandates every data fiduciary to inform the data protection authority about the breach of any personal data where such breach is likely to cause harm to any data principal. This clause only provides limited respite as the data protection authority after receiving notice of such breach has the discretion to determine whether the user should be informed of the breach of their personal data or not.

Lastly, digital lenders rely on automated decision-making for assessing creditworthiness. The PDP bill, while recognising automated decision-making, doesn’t provide adequate safeguards against the harms that can result from such automated decisions, and leaves it for the future data protection authority to specify additional safeguards which will only apply to a subset of personal data deemed to be ‘sensitive personal data’. Neither does the PDP bill entitle the data principal to be informed about the existence of an automated decision-making process, nor does it give them the right to object, seek an explanation, or opt-out from automated decision-making.

Even if the PDP bill, as it stands currently, is enacted, the issues that arise as a result of using automated decision-making for credit assessment will remain.

The solutions

To ensure that financial inclusion does not come at the cost of privacy and consumer welfare, we recommend the following:

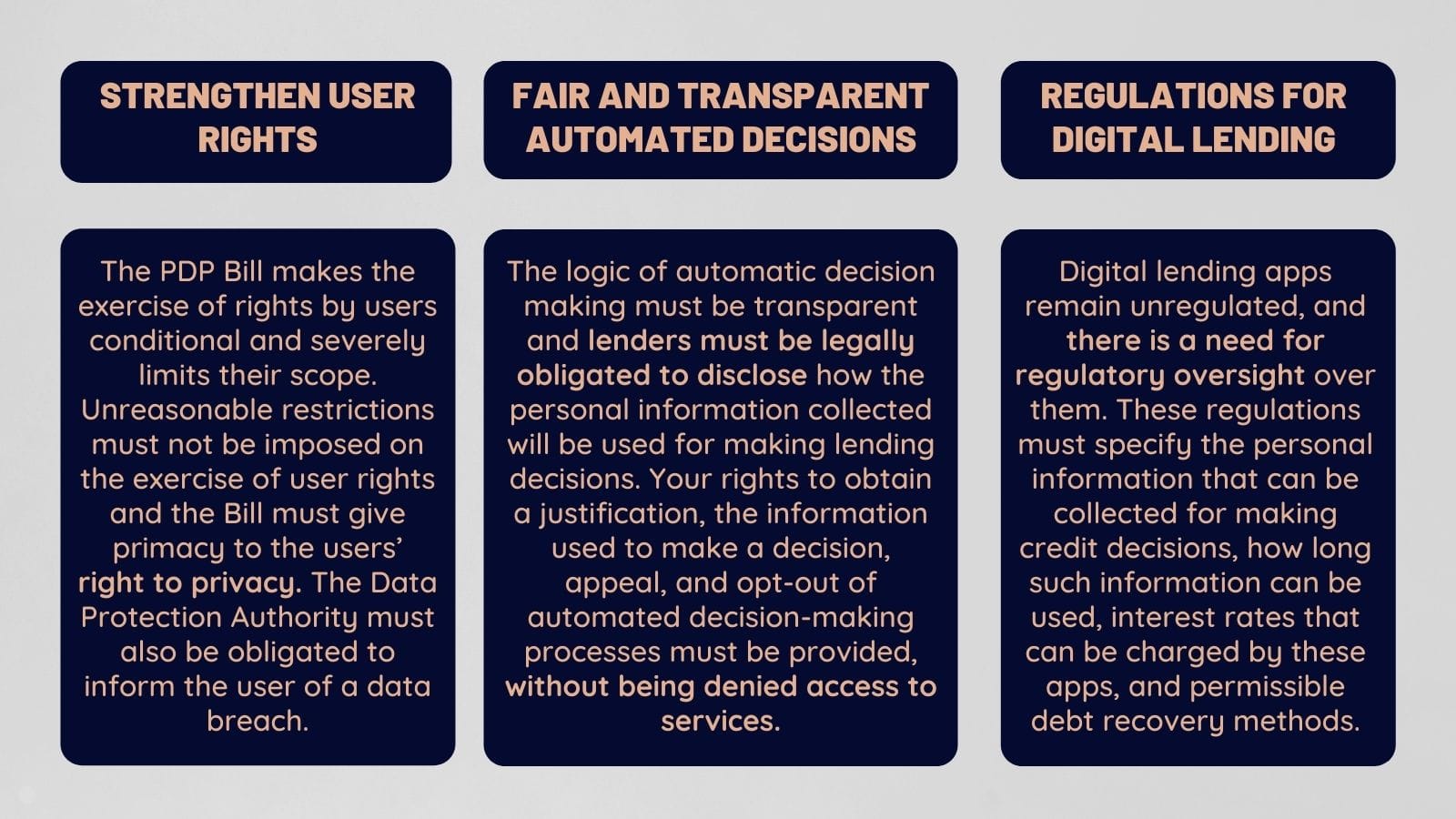

- Strengthen User Rights: The PDP bill makes the exercise of rights by users conditional and severely limits their scope. Unreasonable restrictions must not be imposed on the exercise of rights by users and the bill must give primacy to the users’ right to privacy. Further, the data protection authority should be obligated to inform the user of a data breach in all cases.

- Fair and Transparent Automated Decisions: There must be legal safeguards to protect against the harm caused by automated decision making. The logic of automatic decision making must be transparent and lenders must be legally obligated to disclose how the personal information collected will be used for making lending decisions. To this end, in cases of automated decision-making, the PDP bill must entitle users with the right to obtain a justification, the right to obtain information used to make a decision, the right to appeal, and the right to opt-out of an automated decision-making process without being denied access to services. More broadly, digital lenders must be legally obligated, in cases when the loan is denied, to justify their decision.

- Regulations for Digital Lending: RBI had set up a working group in January 2021 to regulate digital lending through mobile apps which were advised to submit its report in three months. As of yet, digital lending apps remain unregulated. There is a need for regulatory oversight over these apps. The regulations must specify the personal information that can be collected for making credit decisions, how long such information can be used, interest rates that can be charged by these apps, and permissible debt recovery methods.

In order to maintain user privacy and further true financial inclusion, we must strengthen the data rights of users, mandate fair and transparent decision-making processes which do not have a disparate impact on marginalised groups, and enact strong regulations to oversee the digital credit market.

Important documents

1. The Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 as introduced by the Minister for Electronics and Information Technology, Mr. Ravi Shankar Prasad (link)

2. IFF's Public Brief and Analysis of the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 (link)

3. The SaveOurPrivacy Campaign (link)

4. IFF's Explainer on the Account Aggregator framework (link)

This blogpost has been authored by IFF intern Simrandeep Singh and reviewed by IFF staff.