We get a sneak peek into how a self-regulatory body such as one being set up by IAMAI will operate within the IT Intermediary Rules, 2021. To us, while this may not cleanly fit within the present framework, it poses tremendous challenges to artistic expression and diversity ultimately ceding control to Government mandated censorship.

Tl;dr

In light of the recently notified Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021, we decided to provide an explainer on the Internet and Mobile Association of India's toolkit on the implementation of their Code on self-regulation for Online Curated Content providers. In our explainer, we describe the grievance redressal structure proposed by the toolkit, analyse some of the concerns at hand, and explain how the toolkit will enmesh with the Rules.

Context

On February 25th, 2021, the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology notified the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021 (the “Intermediary Rules”). Arguably unconstitutional in their approach, The Intermediary Rules mandate a 3-tier grievance redressal which effectively provides for self censorship of online video streaming platforms, as we have analysed in our last post. A vision of how this would look when operationalised has already been offered up to us through the Self-Regulation Code of Online Curated Content Providers (the, "Code") of the Internet and Mobile Association of India (IAMAI). IAMAI has also come up with a toolkit (prior to the IT Rules were announced) for implementing the Code.

We believe that this form of self regulation will lead to large amounts of self-censorship, given that it will integrate with the oversight function played by the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting. The Self Regulatory Code as made by the IAMAI will need to see changes for it to be brought in line with the fresh requirements with The Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021.

What is the toolkit?

In the context of discussions taking place last year in relation to OTT platforms and their regulation, OTT providers among themselves, under the aegis of the IAMAI, released their own Self-Regulation Code of Online Curated Content Providers (the Code), as far back as September 4th, 2020. The Code aims to, amongst other things,: a) protect the interests of consumers and empower them to make informed choices about content, b) nurture creativity and foster innovation, c) preserve independence of the economy, and d) provide consumers with a mechanism for grievance redressal.

In order to help implement the Code, on February 12th, 2021, i.e., approximately two weeks before the Intermediaries Rules were notified, 17 OTT service providers, under the aegis of the IAMAI, had released a toolkit in respect of the Code. The toolkit recommends the formation of the following bodies

The toolkit recommends the formation of the following bodies:

- IAMAI Secretariat: In consultation with the signatories, the IAMAI shall constitute a secretariat. It shall be composed of representatives from the IAMAI and the signatories, along with any other staff that may be deemed necessary;

- Advisory Panel: Each signatory shall constitute an Advisory Panel to look into complaints when the complainant either is dissatisfied with the decision of the Internal Committee or requests an escalation of a complaint filed with the consumer complaints department of a signatory or the grievance committee proposed by the Code

The powers and responsibilities of the secretariat shall include: a) to provide assistance towards compliance with the Code, b) to develop a process to seek information from signatories about their progress towards compliance, c) to plan and implement consumer awareness programs, and d) to review and update the toolkit periodically.

The toolkit notes that the signatories have agreed to adhere to all applicable laws (see appendix). Signatories must create educational materials for helping their staff learn about compliance and subsequently hold extensive training sessions. Signatories must also take certain steps to improve consumer awareness, such as creating and publishing videos about measures taken in compliance with the Code. Signatories must conduct audits and code compliance reviews each year. Within one year of becoming a signatory, each signatory must submit a self-declaration of compliance to the Secretariat.

What are its legislative and policy origins?

| Document | Recommendations/provisions |

|---|---|

| Self-Regulation Code of Online Curated Content Providers | Regulatory basis for the toolkit; lays down guidelines for age classification, content descriptions, and access controls; provides three-tiered grievance redressal system |

What are the proposed objectives of the toolkit?

The stated objectives of the toolkit are:

- Set out the guiding principles and code of ethics for the reference of the signatories;

- Provide for procedures to effectuate the various provisions of the Code;

- Assist the signatories in fulfilling their commitments and responsibilities as set out in the Code;

- Achieve effective self-regulation goals as envisioned by the Signatories in the Code.

Amit Goenka, the Chairman of the Digital Entertainment Committee of the IAMAI, said that the toolkit is an indication of the commitment of online curated content providers towards augmenting consumer empowerment and creative excellence in the Indian entertainment industry.

What is public opinion on the issue?

The Confederation of Indian Industry has welcomed the toolkit and asked the government to support and endorse it, stating that, “the industry is mature and responsible enough to keep necessary guidelines in mind while creating content”. The Asia Video Industry Association has also welcomed the move, calling the toolkit a useful and important addition to the Indian governance system for Online Curated Content”. However, the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting was not be satisfied with the toolkit, as indicated by reports that the Ministry was considering guidelines for regulating over-the-top platforms. This came to head with the Intermediary Rules which went beyond the Code and this Toolkit.

After the notification of the Intermediary Rules, the president of the IAMAI has stated that the IAMAI welcomed the Intermediary Rules. However, reports have also emerged many OTT platforms are still discussing their responses Rules, with IAMAI collating feedback from industry players on the basis of which a future plan of action shall be devised. The platforms also debated nominating the IAMAI as the self-regulatory body for OTT platforms.

Self-censorship and applicability

An immediate issue is whether the Centre accepted such a model? Answers to Lok Sabha questions reveal that the Ministry felt that the Code, “did not give adequate cognizance to content prohibited under law and there were issues of conflict of interest”. The Minister of Information and Broadcasting, Prakash Javadekar, also explicitly stated that OTT guidelines will soon be implemented, as they soon were. With the notification of the Intermediary Rules, certain provisions of the Toolkit may indeed be retained, however, both the Code and the toolkit will require revision to harmonise with the Rules.

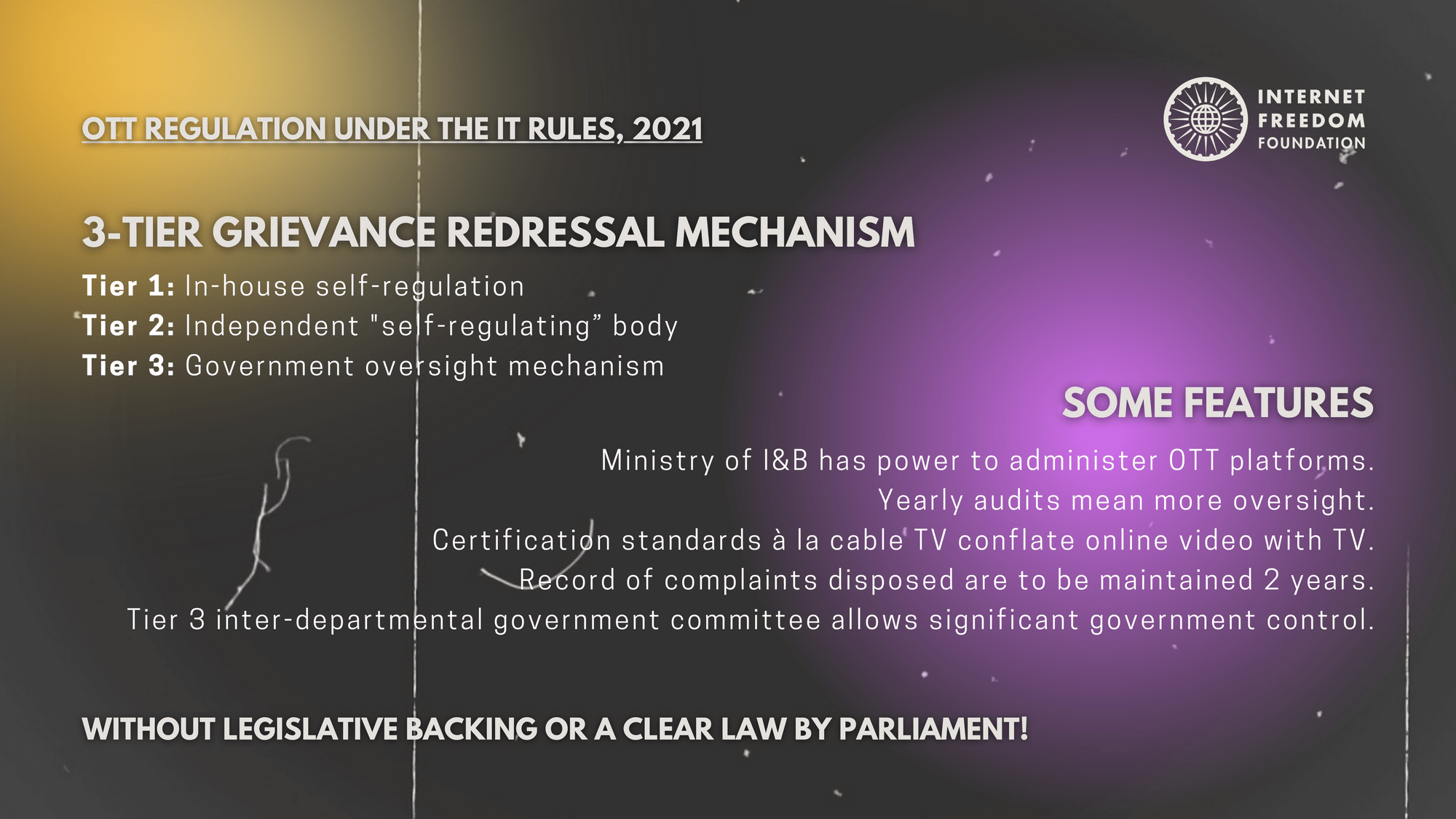

The most important issue is whether the adoption of the Code and the toolkit is a step along the road to self censorship. Even more so in the aftermath of the Intermediary Rules, 2021, the Code is similar to the cable tv model of self-censorship. Through the standards and practices formulated and adopted by the secretariat, the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting will be able to exercise indirect control over content. The yearly audits will provide the Ministry with a further level of oversight over content creators and platforms. Furthermore, under the Code, online content curators will have to maintain a record of each complaint disposed of for two years from the date of disposal, making the threat of ‘inspection’ by the Ministry loom large..

The Rules go beyond the Code by recommending an inter-departmental committee as the third tier of the grievance redressal mechanism, which consists of representatives from the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Ministry of Women and Child Development, Ministry of Law and Justice, Ministry of Home Affairs, Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology, Ministry of External Affairs, Ministry of Defence, etc. This Committee will hear complaints about any decisions taken at the previous two levels, and it will have the power to modify or delete content for “preventing incitement to the commission of a cognisable offence relating to public order”.

This essentially allows the inter-departmental committee a ‘veto-power’ over any content that may be produced. The net effect will be a heavily censored content ecosystem, resulting from both increased self-censorship due to the threat of action being taken as well as the top-down dictats of either the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting or the inter-departmental committee. The Rules also provide the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting with the power to administer OTT platforms. Given that the Rules also suffer from an excessive delegation of powers, a significant level of arbitrariness will now pervade the regulatory landscape, to be exercised at the discretion of the Ministry. More on this below.

Cable TV style regulation

The move towards the adoption of certification based standards and practices à la cable TV regulation incorrectly conflates online video streaming with TV watching. The private nature of online content viewing, where viewer choice is paramount, should imply a different level of oversight than is applied to cable television (and the effect of this regulation is apparent from the stultifying content that generally appears on TV screens). Additionally, the categorisations prescribed by the Code will be drafted and operationalised on the basis of the laws listed in the toolkit, which are themselves extremely vague and allow significant amounts of arbitrariness (especially with classifiers such as ‘seditious’ and ‘obscene content’).

Indeed, the report of the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting’s Expert Committee on Film Certification recommended a more liberalised regime even for film certification, arguing that the Central Board of Film Certification should not act as a ‘moral compass’, and instead limit itself purely to certification (and not dictate modifications and withdrawals). The committee also stated that film viewing is a consensual act, and so regulation should limit itself to a statutory warning, noting that the artistic expression and creative freedom of filmmakers should be protected and any certification should be responsive to social change. Such arguments apply even more to the realm of online content, where the viewer directly chooses the content they wish to consume.

Legal and economic considerations

The chilling effect that such self-censorship would have would be equivalent to pre-censorship by the Ministry. Similar sentiments have been voiced in the judicial system as well. In Gajanan P. Lasure & Anr. vs The Central Board Of Film Certification, the Supreme Court had noted that the unconstitutional restriction or withdrawal of content would be, “tantamount to negation of the rule of law and a surrender to black mail and intimidation” (here the Supreme Court was referring to the protests against the movie Aarakshan), and that it was the, “the duty of the State to protect the freedom of expression since it is a liberty guaranteed against the State''.

Such regulatory models also have other consequences. Contemporary India is a large producer of high quality video content that is watched all over the world. Indeed, it actively competes with other established giants such as the United States of America and South Korea in the field of entertainment. Such a status may be significantly harmed by the imposition of a harsh regulatory environment. Economic effects may also be felt, as the industry generates a large amount of revenue and employment, and is projected to grow at 21.8% per year over the period 2018-2023.

Self-regulation and the intermediary rules

The Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021 have, in the Appendix to the Rules defined a “Code Of Ethics And Procedure And Safeguards In Relation To Digital/Online Media” which shall apply on “applicable entities”. “Applicable entities” as contained in Rule 7 include, “publishers of news and current affairs content”; and “intermediaries which primarily enable the transmission of news and current affairs content”; and “publishers of online curated content”; and, “intermediaries which primarily enable the transmission of online curated content.”

Further, under sub-rule (3) of Rule 8, the Rules lay down a three-tier structure for observance and adherence to the Code which is as follows, “Level I - Self-regulation by the applicable entity”; “Level II - Self-regulation by the self-regulating bodies of the applicable entities”; “Level III - Oversight mechanism by the Central Government.” This oversight mechanism is being created without any clear legislative backing and will now increasingly perform functions similar to those played by the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting for TV regulation. For instance, as per Rule 13(4) this also now includes powers of censorship such as apology scrolls, but also blocking of content!

All of this is being planned to be done without any legislative backing or a clear law made by parliament. It is also patently clear that the provisions of the Code will harmonise with the clauses of the Rules: for example, the IAMAI secretariat is precisely the sort of self-regulating body prescribed by the Code, except with the addition of even more Ministry oversight and an adjudicatory function it will have to play. In conclusion, there are large threats to creativity and diversity which flow from not only the MIB's oversight but also the self-regulatory systems being put in place to operationalise the Intermediary Rules.

Recommendations

In light of the above, here are a few suggestions to address these issues:

- Withdrawal of Rules, Code, and Toolkit: Existing Acts provide the government with sufficient power to address inflammatory content, and so the status quo ante must be preserved (at the very least). Furthermore, as we have explained earlier, the Intermediaries Rules are unconstitutional and so deserve to be recalled. A comprehensive public consultation must also be held before any further versions of the Rules are notified. Since the Self-regulatory code and the toolkit both follow the Rules in spirit, the IAMAI must roll back both of them, and the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting must not endorse the Code.

- Public consultation on Expert Committee: The findings of the Expert Committee must be put through the public consultation process so that the suitable changes can be made to all the regulatory frameworks.

- Emancipatory framework for online content: Online content needs to be given the space to grow, and should not stifled by regressive societal mores and a paranoid government. Thus, an expansive framework for online content must be mandated that allows the creativity of content creators to thrive.

Given the attendant concerns that arise from the above, we requested the Ministry to publish a full consultation timeline over any potential amendments in line with several health precedents for public consultations set in the past.

Presently, no such timeline exists, while the Standing Committee on Information Technology also does not seem to be considering this issue (it does not seem to be in the list of subjects or in the list of sittings - see here). Furthermore, we ask that extensive dialogues be conducted with academics, civil society, digital rights experts and organisations, and technologists, as such groups would provide a unique citizen-centred perspective that would complement the more business or administration friendly inputs of other stakeholders.

Important Documents

- IAMAI's Self-Regulatory toolkit Explainer (link)

- IAMAI's Implementation toolkit to Self-regulation Code (link)

- IAMAI's Self-Regulation Code of Online Curated Content Providers (link)

- Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology's Information Technology (Guidelines For Intermediaries And Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021 (link)