This post was updated on August 16, 2023. See the original version archived here.

Disclaimer: Given this post summarises the discourse in the Parliament on the bill, we will refer to it as DPDPB, 2023 and not as an Act.

tl;dr

The Digital Personal Data Protection Bill, 2023 (DPDPB, 2023) was passed in both Houses of the Parliament during the recently concluded Monsoon Session. The bill that has been in the making for over 6 years was passed after only approximately 2 hours of combined discussion. On August 11, 2023, the DPDPB, 2023 received the President’s assent to become an Act of Parliament. This post summarises the discussions (or the lack thereof) on the bill in both Houses of the Parliament, and sheds light on the disappointing legislative journey of the bill right from the beginning (consultation process) till the end (passage of the bill).

Why should you care?

We have been vocal about our concerns and apprehension about the DPDPB, 2023, since a similar version was put up for public consultation in November, 2022 [Read our public brief on the 2022 version here]. Our fight for a robust, comprehensive, privacy focussed data protection legislation took a hit when the DPDPB, 2023 got introduced in Lok Sabha on August 03, 2023 [Read our statement on the introduction of the DPDPB, 2023 here]. But we were still hopeful for a meaningful, transparent, diverse, and respectful discussion on the Bill. Looking back, it is unfortunate to note that, during the debate, the contribution of Members of Parliament (MPs) representing the incumbent government was perfunctory and the contribution of opposition members was limited due to their absence. To watch the erosion of an institution that is primarily responsible for protecting and advancing our constitutional freedoms and rights, including the right to privacy, is distressing.

Discord on Discourse:

The bill was introduced in the Lok Sabha on August 3, 2023 and was passed on August 7 after only 52 minutes with 9 Members of Parliament taking part in the discussion.

The Digital Personal Data Protection Bill, 2023 has been taken up by the Lok Sabha for consideration and passing. (1/n)https://t.co/nmcTESPN2y pic.twitter.com/6WQEm9tXhH

— On Parliament (@IFFonParliament) August 7, 2023

The members belonged to 7 different political parties with 3 speakers being from the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

After being passed by the Lower House, the bill was taken up for consideration before the Rajya Sabha on August 9, 2023.

The Digital Personal Data Protection Bill, 2023 has been taken up for consideration and passing before the Rajya Sabha at 04:54 PM. (1/n) pic.twitter.com/hVAsZFLAIQ

— On Parliament (@IFFonParliament) August 9, 2023

The legislation was passed by the Upper House after 1 hour 7 minutes of debate with 7 Members speaking on the bill. The members belonged to 6 different political parties with 2 speakers belonging to the YSR Congress.

During their deliberations, both Houses of Parliament raised some crucial issues both in support and opposition of the bill.

Arguments raised in support of the bill:

A total of 9 MPs, including the Minister, voiced support for this bill. Many of the arguments made in favour of the bill need to be further contextualised to demonstrate that there are still shortcomings. To understand these better, read our first-read analysis of the bill here.

Thorough consultation process: While introducing the legislation before the Lok Sabha, the Union Minister for Electronics & Information Technology (IT), Ashwini Vaishnaw, said that the bill had been through a thorough consultation process receiving comments and feedback from both the public and over 40 government Ministries and departments. Even in his address to the Rajya Sabha, the Minister claimed that the bill had been 6 years in the making and the Joint Parliamentary Committee (JPC) had held 100+ meetings on the legislation.

The statements made by the Minister may be accurate, however they do not paint the full picture of the consultation process. When the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) released the draft DPDPB, 2022 for public consultation, the accompanying notice stated that the comments received will not be made public. The Ministry also refused to share the comments received in an RTI application. Further, the consultation process required interested participants to register on the MyGov website in order to be able to provide comments which proved to be a significant hurdle. Even the JPC meetings that the Union Minister alluded to released a different draft of the data protection legislation i.e. the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019. Further, the next draft of the bill, released in 2021, was also withdrawn by the Minister on August 03, 2022. The Minister did not provide substantial reasons for withdrawing the bill, despite it undergoing ample consultation.

Another issue to consider here is the potential circumvention of parliamentary protocol. Reports suggested that members of the Standing Committee on Communications and Information Technology walked out of a meeting adopting its report since it took up aspects of the draft Digital Personal Data Protection Bill, even though it was never formally referred to the committee to examine.

Establishment of the Data Protection Board (DPB) [Clause 18]: The government has hailed the formation of a Data Protection Board as an important step in the success of a data protection regime in India. The Minister stated that creation of the Board will ensure that courts are not overburdened by issues under the Act and only appeals will go before the Telecom Disputes Settlement and Appellate Tribunal (TDSAT) and eventually the Supreme Court.

The DPDPB, 2023 significantly weakens the independence of the DPB by empowering the Union Government to nominate all members of the Board. Further, only adjudicatory and not regulatory powers have been bestowed upon the DPB. Moreover, reasons for choosing TDSAT at the appellate tribunal to which appeals against the decision of the DPB will lie remains unclear.

Notices in 22 languages [Clause 5(3)]: To ensure that the law is made accessible to the entirety of India, Ashwini Vaishnaw said that notice under the DPDPB, 2023 will be issued in all 22 languages listed in the eighth schedule of the Constitution of India.

Key principles of privacy: During his initial address to the Rajya Sabha, the Minister highlighted principles of privacy that the bill fulfils as follows:

👉Purpose limitation: The principle of purpose limitation states that data will only be stored for the limited object it was initially intended for.

👉Data minimisation: Under the principle of data minimisation, the government aims to only store as much data as is necessary for the purpose defined.

👉Principle of accuracy: As per the legislation, all data principals will be allow to ensure that their personal data which is being stored is accurate and incase of any inaccuracy they will be able to approach the data fiduciary to correct the same.

👉Principle of storage limitation: Under storage limitation, the government will only store personal data for a designated period under the object of the data collection has sufficed.

There is little faith in the fact that the bill upholds several of these principles. Some specific examples of where the bill fails to uphold these principles are as follows:

- Purpose limitation: The principle is compromised by the provision related to 'Certain Legitimate Uses' [Clause 7(b)] which allows for the data to be processed without consent of the data principal.

- Data minimisation and Storage Limitation:, The mention of right to erasure is limited by the need to retain information for "compliance with any law for the time being in force" [Clause 12(3)] - which when combined with various sectoral/ other data retention requirements, may result in heavy dilution of this right. Moreover, Clause 17(3) also includes an exemption from Clause 8(7) which obliges a fiduciary to erase personal data/ ask a data processor to erase it once consent is withdrawn (and the purpose is served). Any and all provisions which supposedly uphold principles of privacy, must be read with and in context of the exemption provisions as well as other broad qualifiers.

- Accuracy: Clause 17(3) gives the Union Government the ability to exempt a data fiduciary, including start-ups, from Clause 8(3), which required the data fiduciary to ensure completeness, accuracy and consistency of the personal data. There are neither any safeguards/limitations nor any rationale for why this is allowed.

He also listed the rights accorded to data principals under the bill:

👉Right of access information

👉Right to erasure (which was equated to right to be forgotten by the Minister)

👉Right to grievance redressal

👉Right to nominate in case of death/incapacity

Notably, Clause 17(3) gives the Union Government the ability to exempt data fiduciaries from Clause 11, which pertains to the right of data principals to obtain/ access information about their personal data from the data fiduciary. Thus, the data fiduciary may be exempted from providing the data principal a summary of their personal data being processed and processing activities undertaken, identities of all other fiduciaries and processors with whom the personal data has been shared along with a description of the personal data so shared, and any other information as may be prescribed. Such exemptions, depending on whom they apply to, could significantly dilute this right.

The right to data portability and right to be forgotten have not been included in the Bill despite being present in some previous iterations. Furthermore, the Data Protection Bill, 2021 made a distinction between ‘erasure’ and ‘stopping disclosure' and associated the right to be forgotten with stopping of disclosure. Now the DPDPB, 2023 subsumes this right to be forgotten under the right to erasure. This conflation between the general right to erasure with the right to be forgotten, which is specific to disclosure of personal data, leads to ambiguity. The concern about the right to erasure being diluted due to the need to retain information for ensuring compliance with existing laws has already been outlined previously.

The introduction of duties and accompanying penalties on data principals may have a deterrent effect on data principals. For instance, Clause 15(d) states that it is the duty of a data principal to ensure not to register a false or frivolous grievance or complaint with a data fiduciary or the DPB. While the introduction of a right to seek grievance redressal may be considered notable, the inclusion of such a duty and an associated penalty of up to 10,000 INR for not complying with it is highly likely to create disincentives for reporting genuine grievances.

Tests under Puttaswamy: The government has claimed that the bill follows the three fold privacy test laid down by the Supreme Court in the Puttaswamy judgement i.e. principle of legality, proportionality, & legitimacy. This means that personal data being stored will only be done under a legal basis either under the DPDPB, 2023 or any other law in force and the data stored will be proportional in nature i.e. there will be a rational nexus between the objects and the means adopted to achieve them.

No regulatory overload like previous version: Another MP said that the bill reduced the compliance and regulatory burden for the private sector, this was remarked as a welcome change from previous versions of a prospective data protection law.

Clause 40 lists the 25 specific matters on which the Union government may make rules as well as any other matter, "which is to be or may be prescribed”. Given that a lot of nuance in the bill has been left for prescription in the future through rule making, it may be too soon to say that the bill reduces compliance and regulatory burden.

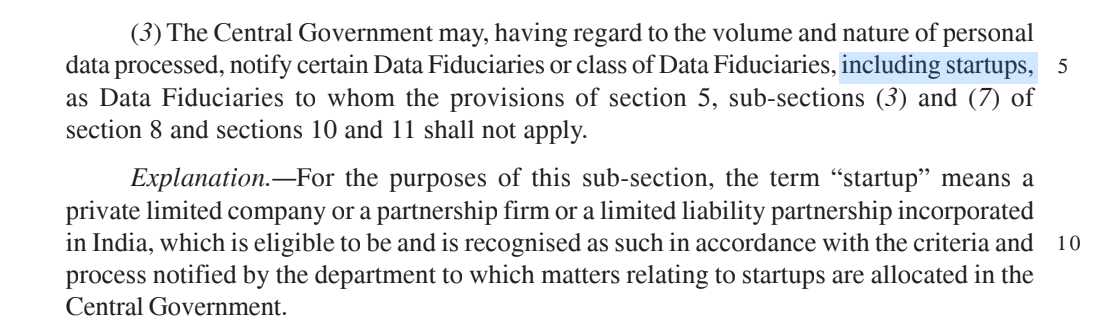

Exemptions to Startups: The exemptions given to startups under Clause 17(3) has also been lauded as a positive move for economic development in the country. While clarifying this clause, the Minister did mention that exemptions to startups are only on compliance & not upon the basic principles of the bill. He also stated that these exemptions will be removed once proof of concept was achieved and the startup was established.

The DPDPB, 2022 provided the Union Government with the power to exempt certain data fiduciaries or class of data fiduciaries from selected provisions. The DPDPB, 2023 retains this provision and specifically includes startups as data fiduciaries that may be exempted by the Union Government. The provisions from which they may be exempt include providing notice to data principals, ensuring completeness, accuracy and consistency of data, erasure of data, additional obligations of significant data fiduciaries, the right to access information about one’s personal data, and “any provision of the Bill for a period of 5 years from its enactment” for a period that has not yet been specified.

Comparing government exemptions under the EU’s GDPR & DPDPB, 2023: In both Houses of Parliament, Ashwini Vaishnaw compared the DPDPB, 2023 with the European Union’s GDPR stating that the latter has 16 exemptions for the government while the DPDPB, 2023 only has 4 (see here and here for Lok Sabha and here and here for Rajya Sabha).

However, this is inaccurate as the bill clubs several separate grounds of exemption, that appear across the sub-sections of Sections 7 and 17, into one

Moreover, even after clubbing the grounds it appears that the bill lists 9 separate grounds of exemptions under Clause 7 (titled as certain legitimate uses) and 11 grounds of exemptions under Clause 17, whereas under the GDPR, Article 23(1) prescribes 10 individual exemptions and includes the qualifier “when such a restriction respects the essence of the fundamental rights and freedoms and is a necessary and proportionate measure in a democratic society to safeguard.”

Additionally exemption under Article 23(1) GDPR only extends to a few provisions whereas the DPDPB, 2023 exempts the government from all provisions of the bill. Under Article 23(2) GDPR, the exemptions are further restricted as it requires the legislature to define parameters while making use of exemptions under Article 23(1) whereas the exemptions under the aforementioned clauses of DPDPB, 2023 have given unchecked grounds to the government, without providing for an additional layer of safeguard.

The DPDPB, 2023 expands the scope of exemption by exempting any government instrumentality (GI) from any processing of data done by the Union Government on information provided to it by an exempted instrumentality. Thus, the data collected by these instrumentalities itself will be exempted.

Principle Based Legislation: While defending the bill, the government said that the legislation is principle based and not was purposely not prescriptive in nature to allow for flexible application. Ashwini Vaishnaw said that the aim of the Union government was to make a technology agnostic bill so continuous amendments are not needed with updates of technology. In his opinion, processes will evolve as rulings of the Board are made and more awareness about the law is spread.

The DPDPB, 2023 lists 25 specific situations for which the Union Government will notify rules at a later stage and also gives itself the leeway to notify rules at a later stage for “any other matter which is to be or may be prescribed”. This limits the ability of stakeholders to meaningfully engage with the draft proposal. This ‘principles-based’ approach adopted by the legislation, wherein detailed provisions will be built out through prescribed rules, may also result in increased ambiguity as well as compliance burden which may be unforeseeable at the moment. The objective of being ‘SARAL’ (simple, accessible, rational and actionable), ‘principles-based’ and ‘nimble’ should not serve as a guise to evade specificity and safeguards as these are not mutually exclusive.

Arguments raised in opposition of the bill

Definitional ambiguity [Clause 2]: Several MPs raised concerns about the removal of the terms like “privacy”, “harm”, and “compensation” and its definition in the DPDPB, 2023. They voiced their concerns about difficulty in assigning liability and providing compensation in the absence of these definitions.

Absence of key rights and principles: MPs questioned why the right to be forgotten and right to data portability was removed in the DPDPB, 2023 when it was part of the 2019 version. In a clarification, an MP refuted the claim made by the Minister that the principle of data minimisation was included in the bill.

Executive control over the DPB [Clause 18]: Many MPs raised questions on the independence of the DPB, citing concerns about the Union government’s powers to nominate all members of the Board, the short duration of members, etc. The sentiment expressed was that the DPB is heavily tilted towards the government.

Blanket Exemptions [Clause 7]: MPs raised concerns around violation of right to privacy and reduced accountability due to the fact that the bill allows the government to exempt any private sector entity and government instrumentality from the application of the provision of law by merely issuing a notification. The MPs particularly cautioned against the misuse of data due to the exemptions provided to data fiduciaries such as startups. Some MPs even felt that the broad and sweeping exemption allows for excessive centralisation of power. Broadly, the MPs urged for narrower exemptions in the bill.

Fresh blocking powers: Several MPs raised concern about unbridled censorship of dissenting opinions as Clause 37(1) which essentially empowers the Union Government to block any content on the internet.

Dilution of the RTI Act, 2005 [Clause 44(3)]: The proposed amendments to the RTI Act was opposed by several MPs and urged for its reconsideration. The MPs also pointed out that the definition of “Personal information” was not included in the RTI Act or the DPDPB, 2023 and urged for its inclusion.

Absence of surveillance reform: MPs in opposition of the bill highlighted that the bill doesn’t bring about a much needed surveillance reform, and instead creates a framework for surveillance of citizens. Several MPs highlighted previous instances of surveillance conducted by the incumbent government and asked if this bill addresses these concerns.

No protection for data processed outside India: Concerns around the data processed outside the country and the lack of protections ensured for harms arising from any misuse or breach was also raised by several MPs.

Weakened consent frameworks: The provision on “certain legitimate uses” [Clause 7] was criticised for giving the government a wide mandate to collect and process the bill.

Conclusion:

The DPDPB, 2023 being passed by Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha, and finally becoming an Act of Parliament, underlines a worrying trend for the future of rights-based legislation in the country. The conduct of an opaque consultation process and sub-version of parliamentary procedures (such as allocation of extremely limited time to speak, no formal referral to a committee for further study) renders the inputs submitted by the public, civil society, parliamentary committees, and other stakeholders of no value. We saw nearly 2 hours of debate across both Houses of Parliament with only 16 Members contributing to the bill. While members of opposition in the Lok Sabha were asked to express their points in a matter of mere minutes, the Rajya Sabha witnessed an almost empty house due to the walk out by the opposition members, resulting in barely any debate on the bill. Notably, while many raised important concerns on the bill, owing to low attendance in the House, very few members opposed the bill and even the amendments proposed by opposition MPs in the Rajya Sabha were not put to a vote as the member proposing the amendment was not present in the House. Disappointingly, the clause by clause voting on the bill was conducted without any opposition, resulting in the Parliamentary record showing no opposition to any of the clauses in the bill. This trend of shirking parliamentary duties being witnessed in the ongoing Monsoon Session paints a worrying picture for further legislation relating to digital rights or even otherwise.

This post was drafted by Saharsh Panjwani, Policy Intern at IFF, with the help of the Policy Team.

Important documents:

- The draft Digital Personal Data Protection Bill, 2023 dated August 3, 2023 (link)

- Public brief on the draft Digital Personal Data Protection Bill, 2022 dated February 16, 2023 (link)

- Living document containing key changes in the DPDPB, 2023 when compared to the DPDPB, 2022 (link)

- First read on the DPDPB, 2023 (link)