tl;dr

The Ministry of Electronics & Information Technology has introduced the draft Digital Personal Data Protection Bill, 2023 before the Parliament today. Below, we present our initial thoughts on the draft proposal and how it compares to the 2022 draft. We strongly urge the Union Government to address the numerous recurring problems with successive iterations that have been raised by civil society stakeholders.

Note: This post has been updated on August 4, 2023.

Background

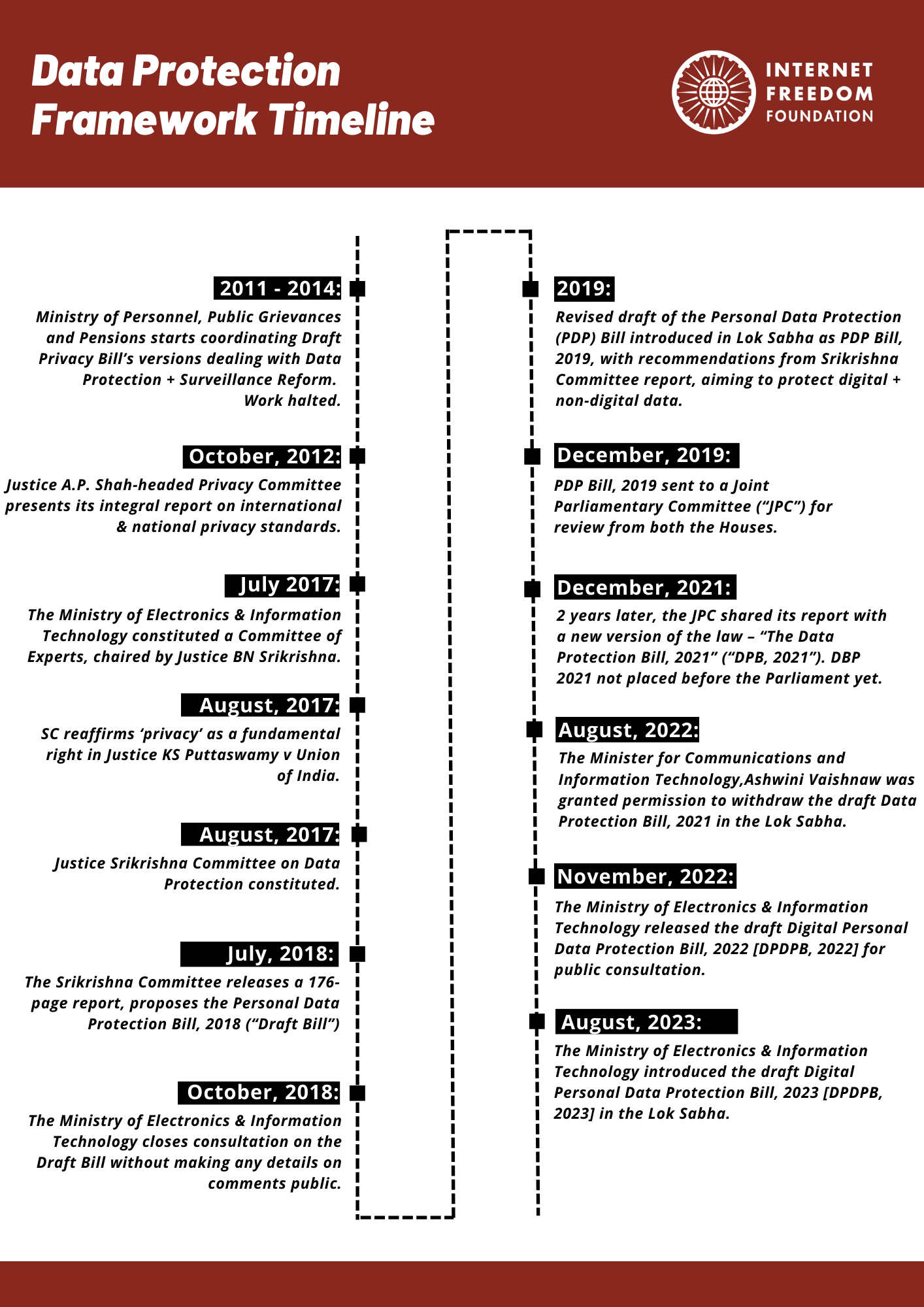

An Expert Committee on Privacy headed by Justice A.P. Shah under the erstwhile Planning Commission presented a report on October 12, 2012 which serves as an influential document on international & national privacy standards.The Expert Committee on Data Protection chaired by Justice BN Srikrishna was constituted by the Ministry for Electronics and Information Technology (“MeitY”) on July 31, 2017. The Committee released its 176 page Report to the MeitY and proposed the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2018 on July 27, 2018. As soon as the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 (“PDPB, 2019”) was introduced in the Parliament on December 11, 2019, it was sent to a Joint Parliamentary Committee (“JPC”) with members from both the Houses for its review and suggestions. After nearly two years and several extensions, the Joint Committee on the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 brought out its report on December 16, 2021. The Report also contained a new version of the law titled, “The Data Protection Bill, 2021” (“DBP, 2021”). However, the DPB, 2021 was withdrawn by the Minister for Communications and Information Technology, Ashwini Vaishnaw on August 3, 2022. The Ministry of Electronics & Information Technology released the draft Digital Personal Data Protection Bill, 2022 (DPDPB, 2022) on November 18, 2022 for public consultation. The notice accompanying the DPDPB, 2022 stated that submissions made as part of the consultation process will not be made public.

Overall analysis

- Consultation and introduction process raises concerns: The notice accompanying the DPDPB, 2022 stated that comments received will not be made public by MeitY. Further, the consultation process required interested participants to register on the MyGov website in order to be able to provide comments which was a significant hurdle. Here, parliamentary procedure also may have been circumvented when the Standing Committee on Information Technology took up the DPDPB, 2023 even though it was not formally referred to it, a move which led the opposition party members of the Standing Committee to walk out from the meeting adopting the report.

- Scope of the bill restricted to exclude publicly available personal data: The DPDPB, 2023 excludes from its application any personal data made publicly available by a data principal or another person to comply with a law. This provision will restrict data principals from protecting their personal data from online scraping.

- Weak notice requirements: Compared to the 2019 & 2021 versions, data fiduciaries do not have to inform principals about the third-parties with whom their data will be shared, the duration for which their data will be stored and if their data will be transferred to other countries.

- Vague non-consensual processing of data permitted: The DPDPB, 2022 allowed the Data Fiduciary to assume consent of the Data Principal if the processing was considered necessary as per certain situations such as for the breakdown of public order, for purposes related to employment, and in public interest. The “deemed consent” clause of DPDPB, 2022 has now been replaced with the “certain legitimate uses” clause with only the public interest sub-clause being removed in DPDPB, 2023.

- Duties and penalties imposed on Data Principals: Duties such as not registering a false or frivolous grievance or complaint have been imposed on the Data Principal, the violation of which could result in penalties (of upto 10,000 INR).

- Vague factors for data transfer: The DPDPB, 2022 did away with the requirement of data localisation contained in the 2019 & 2021 iterations but proposed to put in place an allowlist of countries that would be eligible to receive Indian data. The DPDPB, 2023 further changes this provision to propose that a blocklist of countries will be notified instead to which Indian data may not be transferred. However, the factors based on which it will be determined that a country may or may not be eligible to receive Indian data have not been specified.

- Exemptions created for private actors: The DPDPB, 2022 provided the Union Government with the power to exempt certain data fiduciaries or class of data fiduciaries from selected provisions. The DPDPB, 2023 retains this provision and specifically includes startups as data fiduciaries that may be exempted by the Union Government.

- Exemptions for government widened further: The Union Government had retained the power to exempt any government instrumentality (GI) from the application of the DPDPB, 2022. Additionally, the DPDPB, 2022 also failed to put into place any meaningful safeguards against overbroad surveillance which weakens the right to privacy of Indian citizens. The DPDPB, 2023 has further widened the scope of these exemptions by expanding it to include any processing of data done by the Union Government on information provided to it by an exempted instrumentality. Thus, the data collected by these instrumentalities itself will be exempted.

- Data Protection Board’s independence under question: In the DPDPB, 2022 the Union Government had been empowered to prescribe the strength and composition of the Data Protection Board, the process of selection, terms and conditions of appointment and service, removal of its Chairperson and other Members at a later stage as well as appointing the Chief Executive of the Board. However, the DPDPB, 2023 weakens the DPB further as all appointments will now be made by the Union Government.

- Weakening of the Right to Information Act, 2005: Through amendments, the DPDPB, 2023 removes the public interest exception to disclosure of personal information under the Right to Information Act, 2005.

- Failure to carry out surveillance reform: In addition to providing wide exemptions to the state, the DPDPB, 2023 also fails to put into place any meaningful safeguards against overbroad surveillance which weakens the right to privacy of Indian citizens.

- Power to block access to information introduced: The DPDPB, 2023 has empowered the Union Government to block access to any information if it receives a direction from the DPB to restrict such information in the interest of the general public.

- Important provisions left to future executive rule-making: The DPDPB, 2023 lists 25 specific situations for which the Union Government will notify rules at a later stage and also gives itself the leeway to notify rules at a later stage for “any other matter which is to be or may be prescribed”. This cripples the ability of stakeholders to meaningfully engage with the draft proposal.

Analysis of the key changes in DPDPB, 2023

A. Deemed consent rebranded to “certain legitimate uses”

Clause 7 of the DPDPB, 2023 pertains to “certain legitimate uses”. This clause replaces the “deemed consent” clause of DPDPB, 2022 in name; however, the content of the clause largely remains the same. The clause states that processing of personal data may be done without obtaining the informed consent of the data principal in certain situations. The DPDPB, 2022 was widely criticised for facilitating non-consensual processing of personal data. The DPDPB, 2023 varies from the 2022 iteration by omitting the sub-clause which allowed consent to be deemed in “public interest”. This is a positive development since the sub-clause failed to strictly define the situations in which it may be invoked and thus, could have been widely interpreted leading to misuse.

B. Processing of personal data outside India to be done according to a blocklist

Clause 16 of the DPDPB, 2023 relates to the transfer and processing of personal data outside India. While the 2022 draft provided for a allowlist of countries to which data transfer would be allowed, the DPDPB, 2023 proposes a blocklist of countries to which data transfer would not be allowed. Thus, data transfer will be allowed to all countries which are not on the blocklist. The blocklist will be notified by the Union Government upon the assessment of such factors as it may consider necessary. Here, it is disappointing that an exhaustive list of the necessary factors which the Union Government would consider to arrive at the blocklist have not been included in the DPDPB, 2023. It is essential that the criteria for inclusion on the blocklist be specifically defined to protect against arbitrary standards.

C. Government exemptions expanded

Clause 17(2)(a) of the DPDPB, 2023 expands the scope of the exemptions provided to government instrumentalities and their data processing activities. In the 2022 draft, processing of personal data by notified instrumentalities of the Union Government was exempted from the application of the bill. In DPDPB, 2023, this exemption has been expanded to include any processing of data done by the Union Government on information provided to it by an exempted instrumentality. Thus, any information once collected by an exempted instrumentality and shared with the Union Government would continue to be exempted from the purview of the bill, regardless of whether it is being processed by an exempted instrumentality of the Union Government. Any exemptions sought by government agencies should be granted only if they fulfil the standards of legality, necessity, and proportionality. It is essential that government collection and processing of citizen data is regulated to prevent misuse.

D. Data Protection Board still weak

Chapters 5 and 6 of the DPDPB, 2023 relates to the Data Protection Board (DPB). The provisions related to the DPB have worsened considerably. In the 2022 draft, only the Chairperson of the DPB was to be appointed by the Union Government. However, in DPDPB, 2023, all members of the DPB will now be appointed by the Union Government. This strengthens the criticism that had been levied at previous versions of the bill which questioned the independence of the DPB. It is essential that the Board is independent of executive control. This was also held by the Supreme Court of India in Madras Bar Association vs Union of India (2020) where they stated that, “Dispensation of justice by the Tribunals can be effective only when they function independent of any executive control: this renders them credible and generates public confidence”. Further, the DPDPB, 2023, like its predecessor, only provides adjudicatory powers to the DPB. Here, it is essential that the DPB should also be tasked with regulatory powers that previous iterations of the data protection legislation in 2019 and 2021 tasked the Data Protection Authority with. This will also be keeping in line with supervisory authorities across various jurisdictions which enjoy both adjudicatory and regulatory powers. One positive change which has been made is that the salary, allowances and other terms and conditions of service of the Chairperson and other Members can not be varied to their disadvantage after their appointment.

E. Appeals process revised

The DPDPB, 2023 denotes the Telecom Disputes Settlement and Appellate Tribunal established under section 14 of the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India Act, 1997 as the appellate tribunal to which appeals against the decisions of the DPB will lie. It is unclear why this change has been made and how the Telecom Disputes Settlement and Appellate Tribunal was selected specifically.

F. Scope of the bill restricted to exclude publicly available personal data

Clause 3(c)(ii) of the DPDPB, 2023 states that the provisions of the bill will not apply to any personal data that is made public by the data principal, or if it is disclosed by another person in order to comply with a law. For this provision the illustration gives the example of personal data shared by a data principal on social media. This provision will negatively affect the rights of data principals to protect their data against data processing activities by data processors who scrape data of individuals on the internet. One such example can be of Clearview AI, a controversial firm, which scrapes images of individuals off the internet for its facial recognition technology system. (We want to thank Malavika Raghavan for bringing this point to our notice)

Recommendations

The DPDPB, 2023 reiterates the shortcomings of the DPDPB, 2022 and fails to inculcate several of the meaningful recommendations that had been made during the consultation process which were subsequently made public by the relevant stakeholders. We strongly urge the Union Government to address the numerous recurring problems with successive iterations that have been raised by civil society stakeholders.

In its present form, the DPDPB, 2023 does not sufficiently safeguard the Right to Privacy and must not be enacted. There must be meaningful discussion and debate on the draft bill in the Parliament, including a referral to an appropriate committee which may further seek public inputs in the course of its deliberations to re-architect the bill such that it protects citizens’ privacy from private entities as well as state instrumentalities.

We will continue to monitor the developments around the DPDPB, 2023 and publish further analysis to raise public awareness around our concerns with the draft.