Introduction

This explainer is to help the reader navigate a situation where the police seize and intend to/or demand access to your personal electronic device (PED) such as a mobile phone, laptop, tablet, etc.

Our personal electronic devices are akin to a physical extension of ourselves- we are virtually one with them. Given our increased interaction and the near assimilation of our mind with such devices – laws governing access to PEDs by the police/law enforcement agencies (LEAs) demand scrutiny.

Legal Blueprint

The Criminal Procedure Code, 1973 (Cr.P.C.) provides the manner in which the police and judicial authorities employ powers of search and seizure during a criminal investigation.

Step 1- Seizure

The law broadly empowers -

- The police and judicial authorities to compel a person to produce a PED if it is deemed essential to an investigation;

- The judicial authorities can issue a search warrant (either general or specific) if

i. a person is not complying with the directions under (a);

ii. the person in possession of the PED is unknown; and

iii. to further an investigation. - Currently, the Cr.P.C provides for issuance of a warrant to search a place. However, these are limited to physical spaces like a house, building, tent vessel, etc. There is no provision with respect to accessing a PED as a whole or any specific information/applications on it.

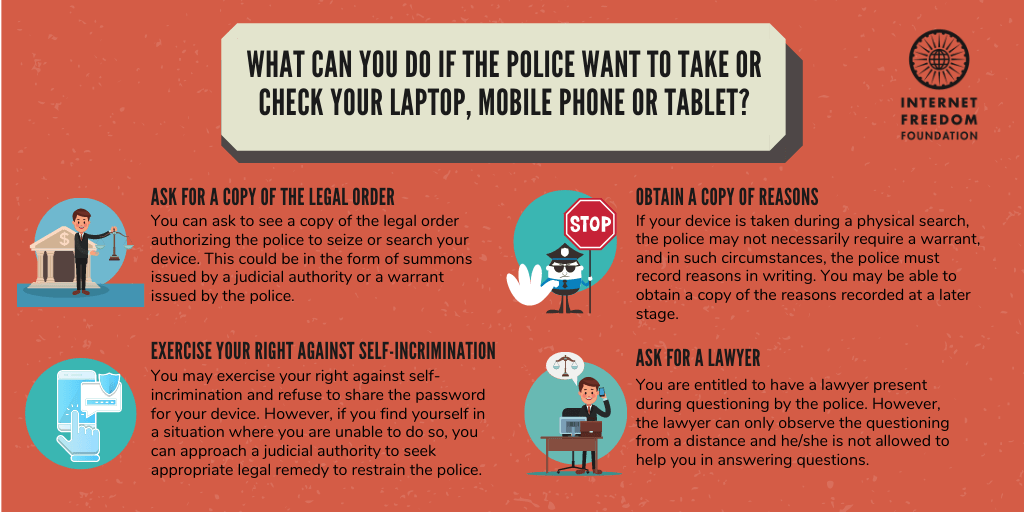

- A police officer can conduct a physical search of a person to seize a PED without a warrant, but afterwards must record his reasons in writing.

- A police officer can seize property (PED) either under the suspicion of being stolen or found in circumstances which creates suspicion regarding committing of an offence.

Thus, within the broad structure of its investigating powers, it seems the police have the power to seize PEDs.

Step 2 – Search

However, as opposed to most physical objects- the seizure of a PED is ineffective unless it can be searched or accessed. The seizure is only the first step- the owner must unlock a device and/or grant police access to the information stored on it. Hence, the statutory framework provides power to the police to seize PEDs, but lacks force in terms of compelling a person to unlock/ allow access to their PEDs.

In practice, a person may refuse to grant the police access to their PEDs and approach a judicial authority to seek an appropriate legal remedy. However, depending upon the scenario, the judicial authority could–

- Agree with a person’s refusal to grant the police access to their PEDs;

- Disagree with a person’s refusal to grant the police access to their PEDs and grant limited and/or complete access to their PEDs;

- Limit the police’s access of a person’s PED to a particular application and/or information on the device. Eg. The police can view WhatsApp communications with person(s) potentially relevant to an investigation, but not family members and friends.

Extent of police powers

In practice, the police while examining a person during an investigation will ask for access (read passwords) to their PEDs. By law, a person is required to answer questions truthfully during an investigation. A failure to do so, may itself maybe a criminal offence.

However, providing information in order to aid an investigation must be prudently balanced with respect to the constitutionally guaranteed right against self-incrimination. A person may refuse to provide information which is potentially self-incriminating, provide password(s) to PEDs which may point to ownership and/or control or knowledge of its contents. In such a scenario, a person may consider refusing to provide such information and subsequently seek an appropriate legal remedy to protect their right against self-incrimination.

A notice maybe given to a person by the police requiring their physical appearance. This is another tool used to seek access to PEDs in the garb of cooperation for the purposes of an investigation.

As stated earlier, people and PEDs have an inalienable bond and these devices contain a range of personal information. Consequently, compelling a person to provide access is a breach of the Right to Privacy under Article 21 of the Constitution. Unless, the police can satisfy the following conditions-

- the direction to compel the disclosure must have a clear legal basis;

- the infringement must be necessary i.e. there should be no less restrictive alternatives available;

- the infringement must be proportionate i.e. it should not cause disproportionate harm to the rights holder; and

- the infringement should have a legitimate aim.

Consequently, if the police are unable to satisfy these four criteria- access to the PED is illegal.

Issues to consider

Giving access to a PED is akin to allowing the police to search your house. However, providing the house keys doesn’t necessarily imply they have access to your personal documents, the family jewels in your parent’s safe or have the right to peep over your garden fence and into your neighbour’s home.

Following are certain limitations to the police powers of search and seizure.

A PED may require one password to access, but several other passwords could be necessary to unlock applications/software within it. Thus, raising certain vital questions-

- What is the definition of access to a PED under Cr.P.C?

- What is the scope of the access – is it specific, limited and/or complete?

- What is the nature of the access- is it limited to information sought as per a warrant, is it only a person’s personal information, general information or anonymised information?

- Does access to a person’s PED mean the police can also gather a third person’s personal information (without their consent) from the device or from an application on it?

- Are there limits to which a person can consent to granting the police access to a PED or does consent qualify as absolute?

The Social Network conundrum

Searching or accessing a device is different from a physical space. In theory, if access is granted to a PED- it will be unlimited, unless categorically restricted. This gives rise to a precarious situation where searching a PED provides disproportionate access to a person’s social networking accounts (Whatsapp, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, etc.) and other information which may or may not be relevant for the police investigation.

The key issue here is - accessing a social networking application on a PED is a single point within a larger network. Hence, the police are now accessing personal information of several persons who have not consented to part with it or may not have any co-relation to an investigation.

Arguably, the purpose of accessing a PED is to extract as much information to aid an investigation. However, even as a justifiable corollary -the power to search by its very nature is limited to the person whose PED is being accessed.

Reality check!

Any person is likely to buckle under pressure from the police and simply give up their passwords to their PEDs, social media accounts, etc. Now that you have read this explainer, hopefully you are better informed to handle the situation.

Lawyers are still not allowed to be physically present during questioning by the police. However, a lawyer can accompany a person and observe the questioning, but cannot assist him in answering any questions.

A person cannot record the event when they are being questioned by the police. The only version of the interaction officially reported is the one by the police officer. Thus, there is usually a slim chance to negate the evidence obtained by means which are strictly not in accordance with law.

Conclusion

An investigation can lead to many delicate situations where- either a person feels their rights are violated or the police allege non-cooperation. Balancing the rights of persons vis-à-vis allowing the police to conduct investigations in various scenarios cannot be solved by applying uniform solutions. Hence, the rights and duties of both sides must strike a balance for a harmonious outcome within the confines of the law.

(This explainer has been authored by Advocate Amrit Grewal who generously volunteered his time for this.)